Lucio Pozzi in Conversation with David Ebony Zoom Event Recording Transcript

Wednesday 8 December 2021, 1-2:30 pm EST

Hal: Welcome to the conversation between Lucio Pozzi and David Ebony. Hal

Bromm here, it's a pleasure to have you with us! Thanks to Katie Svensson for

coordinating this event. For your information, the talk is being recorded and will

be uploaded to the gallery's YouTube site and also will be on our website. If you

have questions or comments, please write them in the chat box and we will aim to

respond toward the end of the event.

Today we will be discussing Lucio Pozzi's

prolific career in conjunction with his current exhibition "Time and Again" here

at the gallery on view through late January. The exhibition features lushly

colorful new paintings in 'conversation' with early 70s reductivist diptychs.

Lucio was born in Milan and moved to the United States as a guest of the

Harvard International Seminar. Though foremost a painter, Lucio considers

writing, drawing, and sculpture to be valuable tools in his work. He has taught

and lectured extensively at institutions including Cooper Union, Yale, Princeton,

Maryland Institute and SVA. Lucio Pozzi has worked with this gallery since its

founding in 1975, and in over four decades has participated in numerous

installations and exhibitions here, several of these will be discussed today. He

currently divides his time between Hudson, New York and Valeggio, Italy. We're

honored to be joined by David Ebony a renowned art critic, curator, art

historian, and friend. He received his MA in art history from Hunter College

studying with theorist Rosalind Krauss and artist Robert Morris. David is

currently a contributing editor of Art in America and a frequent contributor to

Artnet News and Yale University Press online, among other publications. David

is a member of AICA and the author of numerous artist monographs.

Lucio,

David, Katie and I are delighted to have you with us today!

David, would you like

to begin the conversation?

David: Hal, thank you very much for that introduction; it was very nice. and

I'm so delighted to be here via zoom with Lucio Pozzi who is one of the art

world's best kept secrets, I say, because he's a cult figure in the art world.

Those in the know, know his work. He's been around for a long, long time and

he's never been predictable; he always changes; he is never doing the same

thing over and over. He's got an incredibly multi-faceted career that we

should all know better, and I hope that this presentation will open up some

new audiences for Lucio's work because it's incredibly brilliant, beautiful, and

profound. How's that Lucio for an introduction?

Lucio: I really don't know what to say, how are you?

So, why are you a best-kept secret? What has taken you so long to become a

household name? Why are you keeping us waiting?

I have no idea. I just work as much as I can and bless every day I have the energy

and the ideas to make art on all levels from the big, to the small, from the lasting to

the ephemeral and make my dialogue with the world possible. And I try to make it

so that spectators can be as creative as they can when they approach my art, so the

door is always open.

The door is always open. Yes. That's a beautiful statement. Tell us a little bit

about how you got involved in the art world. Tell us about your background

and how you started to make art.

My mother was divorced from my father and after the war she married the British

sculptor Michael Noble, who influenced me very deeply. He taught me very many

things that I still practice in art. And he being a sculptor I sort of decided to

become a painter and when eventually I moved to New York, I approached art in a

way that was essential for my learning.

Essential in what way?

Coming from Italy, it was very theoretical. In the United States I touched firsthand

that which I had only read about, which is pragmatism, the William James kind of

pragmatism. And I really saw firsthand by meeting artists how to approach art in a

direct way instead of filtering it through too much of an abstract discourse.

What was your first attraction in art when you came to the U.S. Were you

already making art in Italy, or did you first make art when you came to the

United States?

I was making art and already exhibiting it in Italy and I was part of a group of

people who looked upon American art as a model. I was living in Rome, and we

occasionally would see one Rothko, one Ellsworth Kelly, one Newman. At some

center for the arts, a Roma-New York Association, something like that,

occasionally these things would be seen. But in Rome there was Cy Twombly, and

he was a big influence on many of us.

Did you know him personally?

The gallerist I was showing with, Topazia Alliata, brought me once for tea at the

palazzo where he was living with his wife at the time. I remember this big palazzo

with furniture and incredible monumental curtains and paintings and whatever.

And I had.., you know, I was very young, and he was a mature artist and so I just

listened to the exchange between him and other people. I could not say I have met

him but I had an interesting listening situation with him.

Your work is so extraordinary in that it's both minimalism and maximalism,

but your first attraction was to minimalism. What is your feeling about that,

your relationship to minimalism?

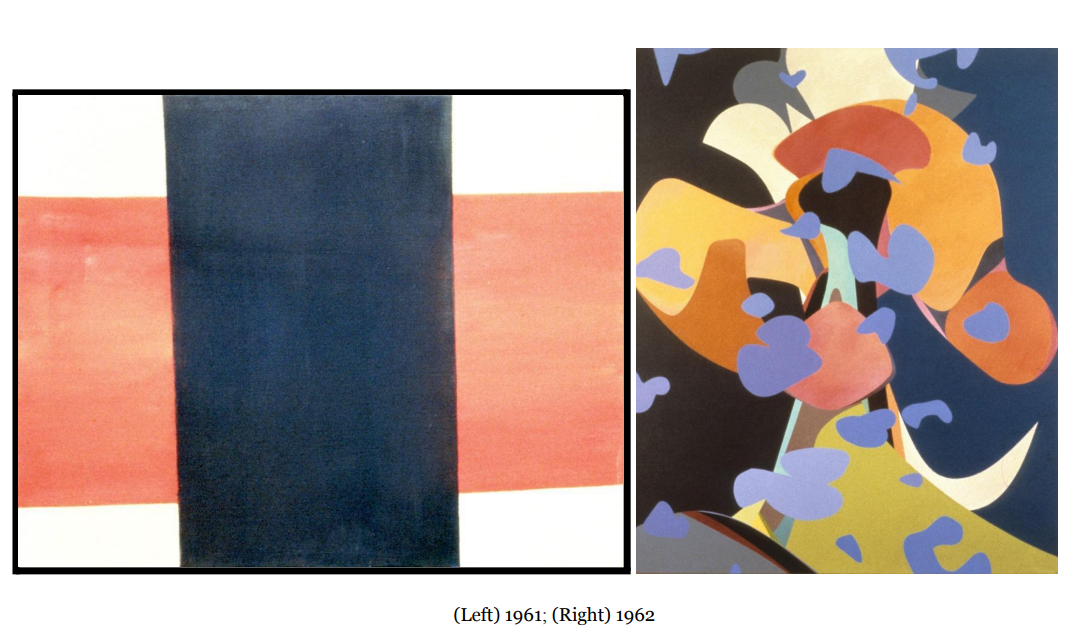

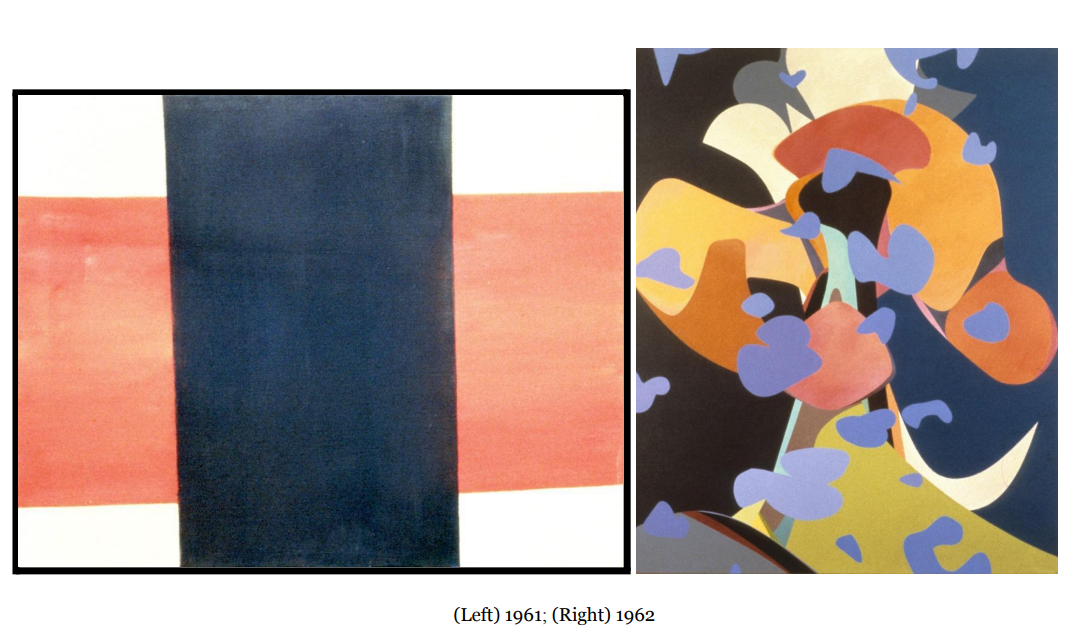

The somehow minimal painting you see on the left side of the screen was in 1961

and it was a basic experience for me because I reduced the terms of painting to the

utmost; but in it I also hinted by overlap at a third dimensionality. I refused all my

life to flatten painting in an exclusive manner. So, from there I extended my

imagination, my painterly imagination, to the extreme and shortly after doing that

painting which has two bars, one red and one black - I calleds it MCH as a homage

to Malevich - I also, shortly after, I did that other much more baroque painting you

see on the right, in which you see some blobs floating over some imaginary shapes

and where the three- dimensionality is not any more hinted at but actually is

practiced in a more obvious way. The dichotomy between that which seems more

abstract, and that which seems less abstract is something that has accompanied me

all my life. I am very keen on that because when I know something too well, I need

to switch to something that gives me more panic and excitement. And then when I

begin to know that more, then I switch back maybe to something which is more

exciting at the time, even of a kind that I might have already touched upon but had

become almost forgotten. This zigzag is crucial to my practice.

This is an opportunity to talk about the fact that at one point around 30 years ago

Merrill Wagner asked me to join the American Abstract Artists' association. And I

was accepted by them at the condition that they would know that I concurrently do

things that would seem abstract and things that would appear to be more realistic or

figurative and that by them accepting me meant also a redefinition of what

abstraction is.

Is that when you met Emily Mason? I've worked with Emily on a number of

books, and her mother Alice Trumbull Mason was one of the founders of that

organization, correct?

Yes, Emily and her husband Wolf Kahn were among the first American artists I

met in Rome. When I came to New York I stayed in their loft, which was on

Broadway, one of the first places I stayed in when I came over. They became close

friends and we talked about painting very much.

But it was Merrill Wagner who invited you to join that group?

Merrill Wagner I met later, in the 70’s, and I think I met her and Robert Ryman, her

husband, through my starting to exhibit at the John Weber gallery.

John Weber was the center of so much avant-garde work at that time. Maybe

we should show some more works.

Yes.

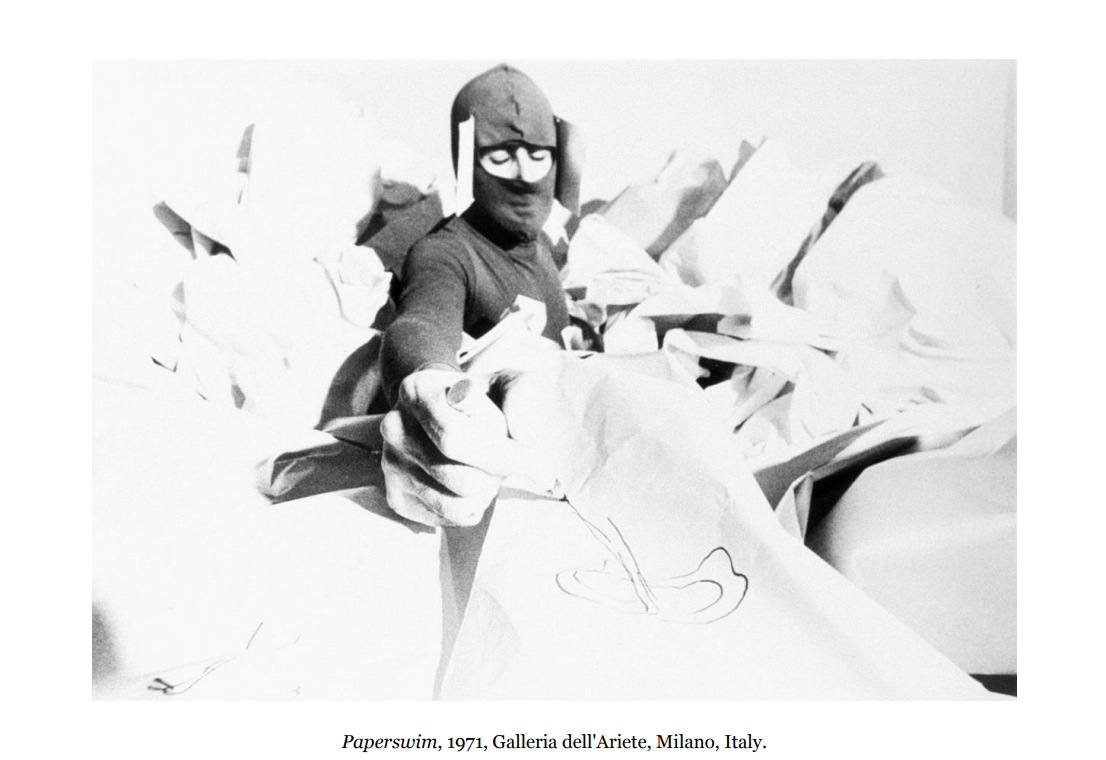

Because your “practice”, as they say these days, was multifaceted, it also

included performance. All along you had a performative element to many of

the projects that you did. So, was this one of the first, called Paperswim from

1971?

Yes, I did Paperswim in 1971 in Milan before coming to the States and then I did it

again at Tyler School of the Arts in 1987 and then I did the third one at DIA Center

for the Arts on Mercer Street in New York in 1991 and a big video was taken of it

at the time. Paperswim was my answer to.., I was insisting on the importance of

painting. As you know, painting is.., painters are told that painting is dead every 10

years more or less since 1890. And so I found myself caught into one of those

fashions in the late 60s and people told me that painting was dead, that there was a

certain Joseph Beuys doing actions in Germany, and so, I was having a show in a

gallery in Milan (1) where Robert Rauschenberg and other Americans were

showing and I told myself “I'll prove that painting extends in all kinds of ways”,

also in this thing which they called Actions at the time - no one was talking of

Performance then. (2)

I had been very fascinated by the history of theater in Italy and in Europe and I

called these things pantomimes, which is an old performance art that starts even

before the medieval times in all the civilizations of the world.

So,

I crumpled all kinds of unprinted newsprint paper, which I discovered

newspapers were throwing out before changing the press rollers. And I crawled

underneath wearing blinders to symbolize the oblivion of the world that artists,

painters especially, have when they paint and I dove underneath wearing this

leotard and came out…

Is that you ?

That's me. Every minute or two I came out like Venus from the sea and made a

mysterious mark on the paper and then dove underneath. I then started doing

performances within the absurd office hours, which I still do. Eight hours. This was

an eight-hour performance. It leaves you exhausted as you can possibly be, and it is

an interesting thing to do.

I wonder if Marina Abramovic knows about this work?

At the time I met Marina Abramovic in New York, later on, I was introduced to her

and she was introduced to me as co-performers, but I was insisting on painting, so,

I was not labeled as a performer. I was labeled as a painter, and we talked a little bit

and she took off in her career in one way and I took off in mine in another. (3)

When you did this performance where is the audience? Is this on a stage, or

how is the audience involved?

The first time it was in a storefront next to the gallery (4) and the performance I did

after that one, I meant to do one every day for five days, but the one after this one

was that I was doing a shootout. There were three actors walking with the

passers-by in the street and in the street I was inviting people to come in, “come in!

every half an hour there will be a shootout. It will be an execution”, and the actors

came in with the audience. There were each time 10 people more or less,

passers-by or art-interested viewers, and at the half hour exactly, two actors would

arrest the third actor, drag him or her against the wall and shoot this person with a

blank and then drag the corpse in the back of the... in the back store. So, in the

middle of this eight hours of performance the police came and arrested me and

started interrogating me about whether I was a Communist. So, my performance

was interrupted, and I spent the night with the police trying to explain what I was

doing, and they did not know what an artwork for aesthetic purpose meant. I

remember the policeman asking me from behind a big typewriter "How do you

spell aesthetic?" but then I got scared around two o'clock at night because there

was an anarchist who had been ‘suicided’ by the... from the window of the same

office a couple of months before. So, even though I wanted to be very independent

from my father I called him at two o'clock at night and said “listen, if you know

any general or any official who could drag me out of here, it would be better”,

because I was afraid. That was very scary.

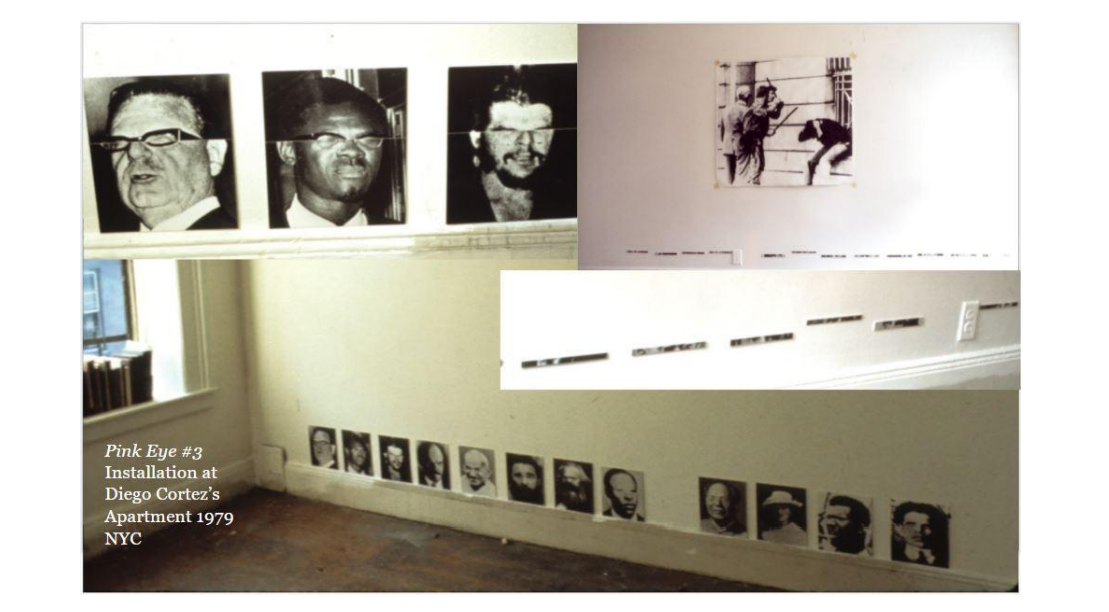

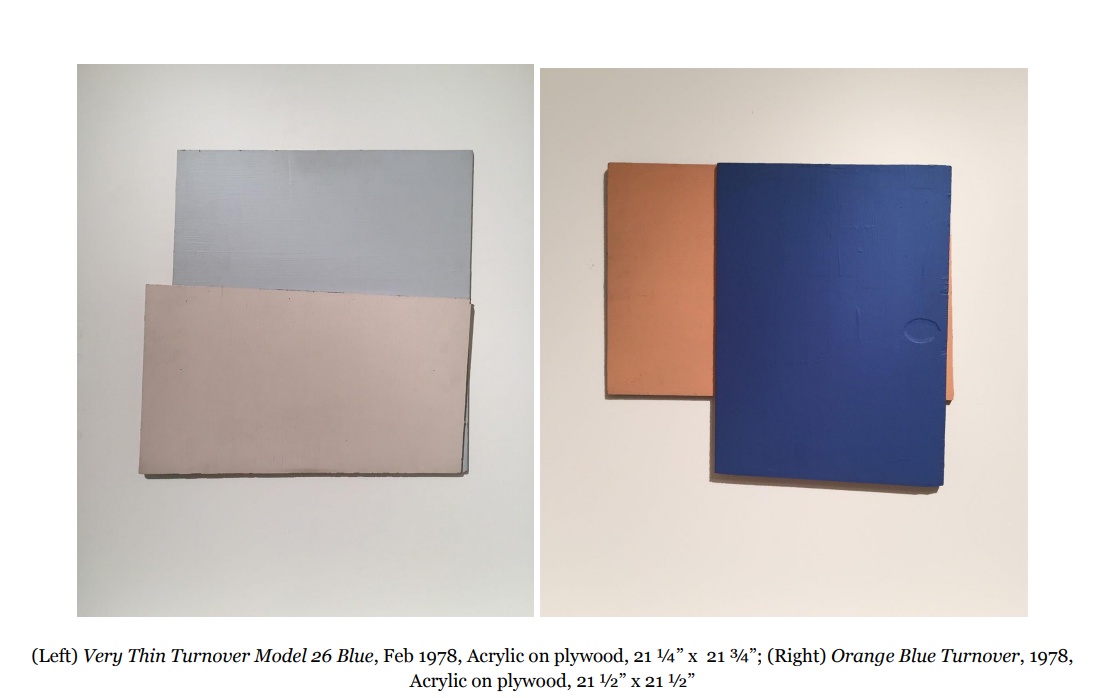

Wow that's a great story, and this leads to your political installations, like the

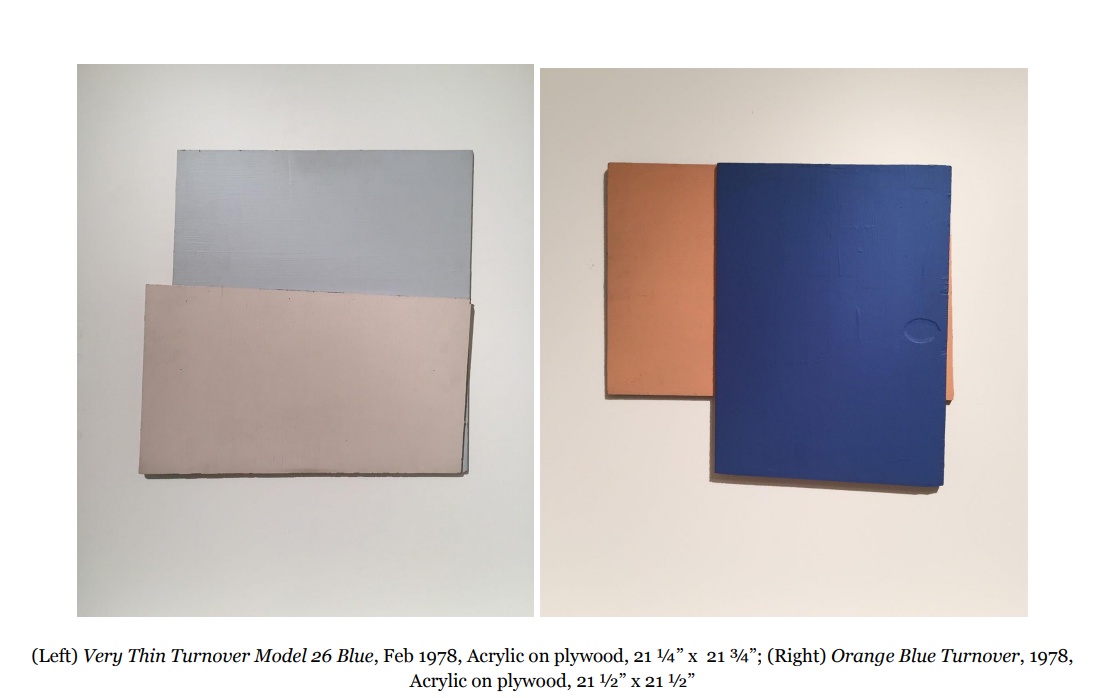

next--is it the next slide? Oh no this is the Turnovers. We'll go back and forth I

guess. Yes this was the one I was thinking of.

Politics are inevitable and I think that even when you do something which is called

abstract, standing for the autonomy of artistic thought and for invention is political.

In this case, the images you see, it was Diego Cortez's early gallery in his

apartment in the Lower East Side.

The late wonderful, great Diego Cortez!

A great entrepreneur and great artist. I've many works of his that at one point he

had asked me to return to him because a collector wanted them. And they are in my

warehouse in Hudson, but I cannot find them; they're mixed in the middle of

things. I have a print we did together.

And now in this case, there was an alignment of leaders’ heads, from pacifists to

leftist leaders, on the bottom of the wall. On the opposite wall, there were the

removed eyes on strips, matching the slit left from their removal and above the

strips there was a gentleman in a business suit watching two other gentlemen

beating a third one. And his eye was dabbed with pink and I called this situation

Pink Eye that hinted at pinko, which was what the sympathizers of Communism

were accused of being during the McCarthy era. And, also, because pink eye is a

disease of the eye, it's a name for conjunctivitis.

When people ask me what the meaning of a work is whether it is, quote unquote,

“abstract” or whether it is more, quote unquote, pointedly “figurative” or seems to

have explainable meanings, I normally refuse to explain, because I like art to have

different explanations. I like the explanations to be generated by the spectators.

The spectators become creative and creatively misunderstand or re-understand my

art. Often I don't know what the meaning is myself (5).

But in some cases, like this particular work is, it's a historical piece, you know,

not only within recent art history but you're dealing with historical events. So

there for new generations is need of some sort of explanation of what it is.

Like why did you choose the three figures that we see on the left?

Those three figures are among the leaders of the left, leftists, their eyes were

removed and replaced across the wall from where they were aligned. Why, I will

not explain. I do not know the exact meaning of this, there are millions of

explanations available and I like everybody to contribute their own ideas, if they

wish.

Yes, please ask questions: the audience should please write in some questions

that they might have for Lucio. But I also wanted to talk about this

installation because it's characteristic in a way of the kinds of unusual,

unexpected installations that you've done over the years where you have these

photos way at the bottom, only the poster is at eye level, but what is your

modus operandi for doing such, I guess, eccentric installations?

I like to have tools that are flexible (6). In this case and as you will see in other

works also that we see today or at least some of them, here I use a very simple tool,

very simplistic tool: there is something which is located; there's something which

is cut off and is relocated somewhere. So, this relocation can happen with paint

applied on wood, it can happen with photographs and have different variations of

meaning available. Relocation is one of these tools. In the Turnovers, you see a

piece of plywood that has been painted on both sides, has been cut in two, and a

part is turned over and relocated, applied on top of the original piece of wood. The

two colors mix with vertical brushstrokes and horizontal brushstrokes rearranging

themselves, that’s just by taste and by some kind of mathematical game I might

play. The relocation is one of the things that I can rely on if I want to do something.

And the something I want to do may come from the terms of circumstances in my

mind or from how.... from a request from somebody or from a desire that the

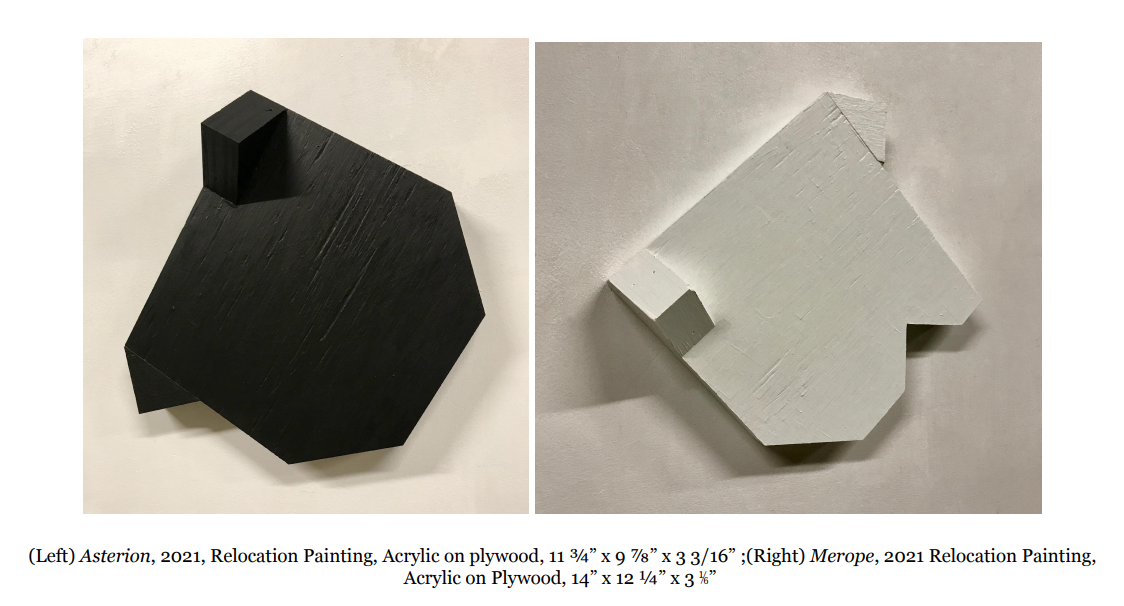

location might call for. Like, for instance, in the show that’s at Hal Bromm

currently now, there was a white cabinet against the wall and there was a black

cabinet. So, I analyzed the given, then called back the idea of relocation to make

two painted sculptures that I hung on top of the wall behind the cabinets: I put the

black on top of the white cabinet and the white above the black.

And we'll see them; we'll be looking at that in a moment.

See them later on.

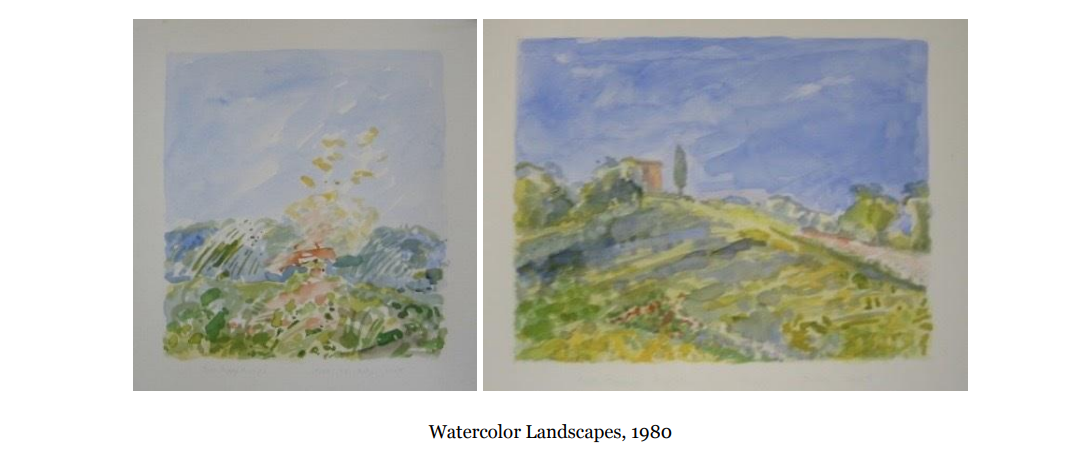

Yes, I just wanted to point out this painting behind me it reminds me of a

Turnover piece that has exploded from the top. You painted this in 1983 and

it's called The Gush and I always admire this painting because it sort of

represents this multi-faceted thing that you do. As we can see from these

Turnover pieces, to the watercolors that you do at the same time, that you've

always done throughout your career, like these. How do you, how do you

reconcile those two endeavors?

It's inevitable (7) that I am myself as I challenge myself to all kinds of visual

languages and it's inevitable that my time and my place seep into the works I do. I

think one cannot be other than oneself. So, as I stretch myself, as I stretch the links

between the different endeavors I engage in, all kinds of connections reveal

themselves. Hopefully without my even knowing them. If you look carefully at the

formats and the forms that I engage in you can see incredible connections. They

become obvious if one spends time to look for them. They're not formulas, they're

forms. And color relationships are often consistent. Colors are a choice that comes

without my deciding. I don't pre-decide my colors. I try to always change my sense

of colors but I'm resigned to the fact that I have a kind of range of colors that keeps

popping out no matter what I do.

What are they?

I wouldn’t know how to name them.

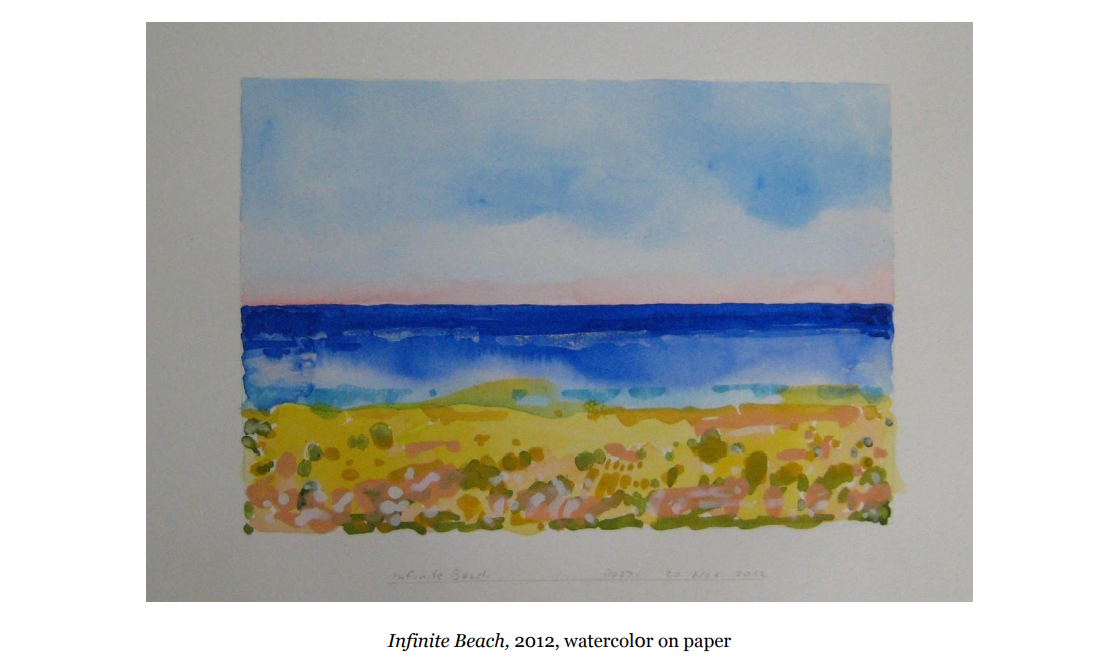

In this case, there's a dualism which is: on top there's the blue sky and underneath

all kinds of blobs that are arranged in formations that may be identified as bushes

or grass or whatever. There are a couple of buildings in both these paintings.

I don't go beyond that. I don't explain much. I try to develop my sensibility as

challenged by whatever theme I happen to be engaged in. The theme is given by

my alternating one way of making art to another one, so that I keep on the edge all

the time. Then I can never settle. I don't feel good if I am settled into a way that

guarantees somehow my research or my exploration.

What about your environment? What about the place where you are in a

specific moment?

Yes, that surely affects me. It surely affects me because it affects me as a site but

also as a cultural site. But I don't enumerate the conditions by which my work

develops, I don't have time. The situation, I mean, is its truth.

Do you remember where these were painted? Where this was painted?

In Sardinia, it's a seascape. The other ones you showed before were in the

countryside somewhere.

And you're painting on site? You painted this on the beach. You were on the

beach? These were not made from photographs?

No, I was sitting there, (8) and I had my watercolors and I tried to observe what I

saw. But there's no way for all the universe of mine and everybody's history and

imagination not to pour into the making of any work of art. There's no way. I'm not

seeking original formulas, I'm seeking the single experience and the intrinsic value,

the intensity, of every work. I feel that if I generalize too much or if I give myself

themes that are too restrictive, I will lose the intensity and I am very keen on

daring myself always to the utmost. To start making watercolors or making

apparent still lives with flowers like the one behind me, was breaking very many

taboos, was daring myself to go as far as I could into understanding painting and

sensibility, and trying to reach for that which is unreachable which is the intensity.

Next Image.

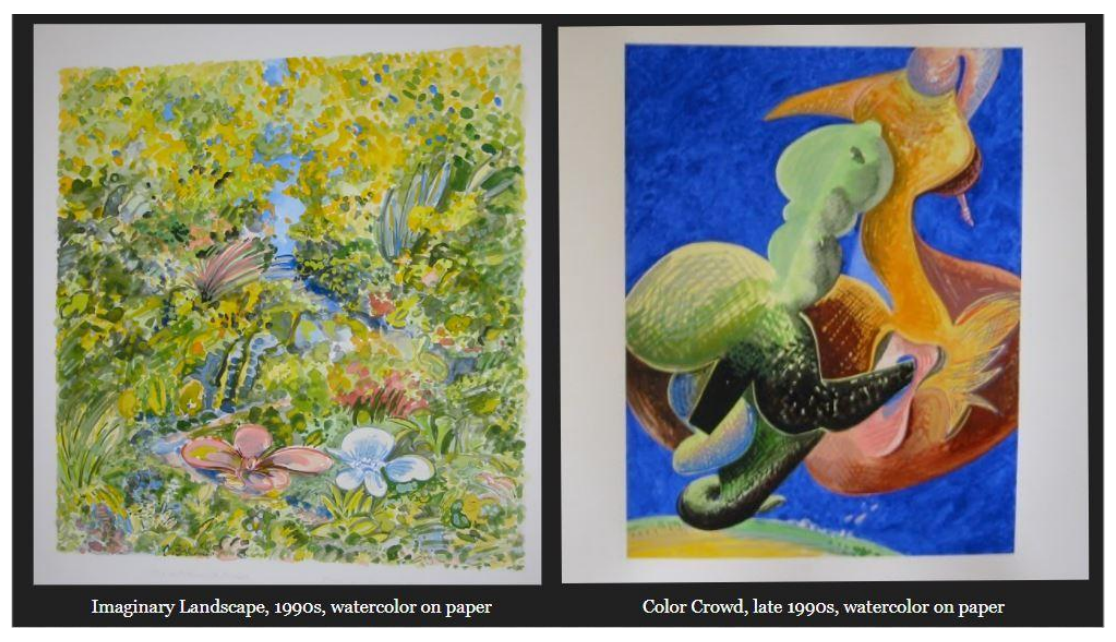

So this is the dichotomy right here with your watercolors: the one on the left is

of an intelligible landscape and on the right this is some sort of a unconscious

quasi-Surrealist approach.

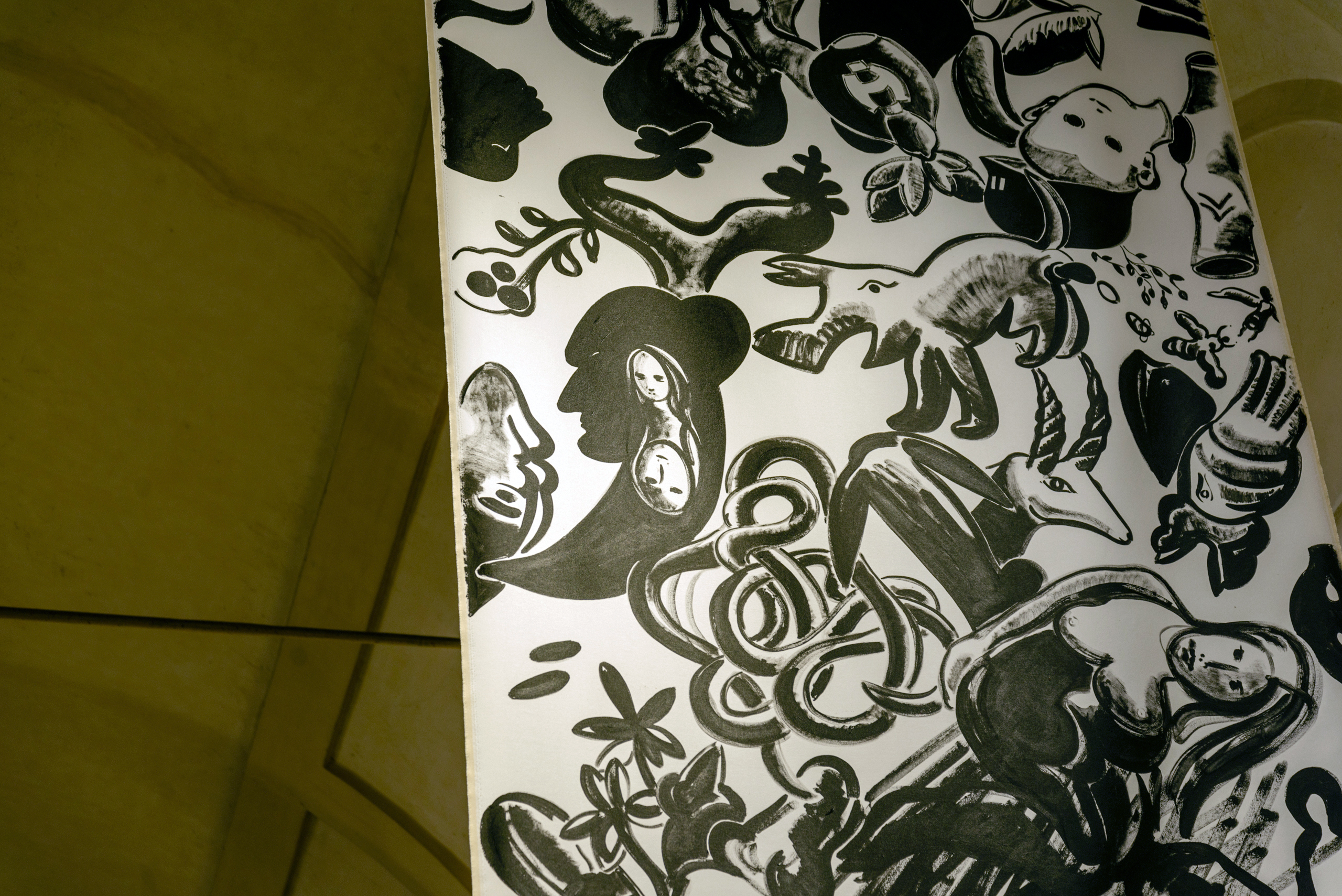

Surrealism (9) is inevitable, I think, for everybody. If you look at much

contemporary art, Surrealism has affected us all without us knowing. I don't know

how, like very many of the things I do, I don't know the outcome. I start with some

images and then start painting and see what happens and the shapes transform

themselves into one way or another and I'm as surprised at the end result as anyone

who sees it for the first time. This scene here seems to be fairly erotic and

science-fictionish and I see a kind of, a Malevich kind of black rectangle put in as a

tail of the greenish being. But don't ask me how it happened and what I meant

because I am a spectator while I paint.

Does it have to do with your mood at the time? Is it something about your

psychic state where you're drawn to do an imaginary landscape and then this

the imaginary interior, or trying to convey some sort of interior mindset?

More than conveying, I’m trying to read, to be witness to the state of mind. That's a

very good question. The mood always affects me. There's no way for it not to, and

I would like very much for the spectators, for whoever looks to be able to project

their own mood, as a reflection of what I do, and not try to interpret what I meant

but try to interpret what my work is causing in them.

And it's not exactly a dream image.

I often wonder about this. I have often spoken in the past with the [late]

Brazilian artist Tunga about his inspiration that came from the hypnagogic

state. You know, the state between consciousness and dream, the dream state

before you fall asleep.

Yes, before I do anything - before I do a performance, before I get into inventing an

installation, before I paint - I meditate and I put myself in an altered state. Then

always, instead of counting myself back into reality, I stop the count-down and

enter into the activity of whatever situation I'm in.

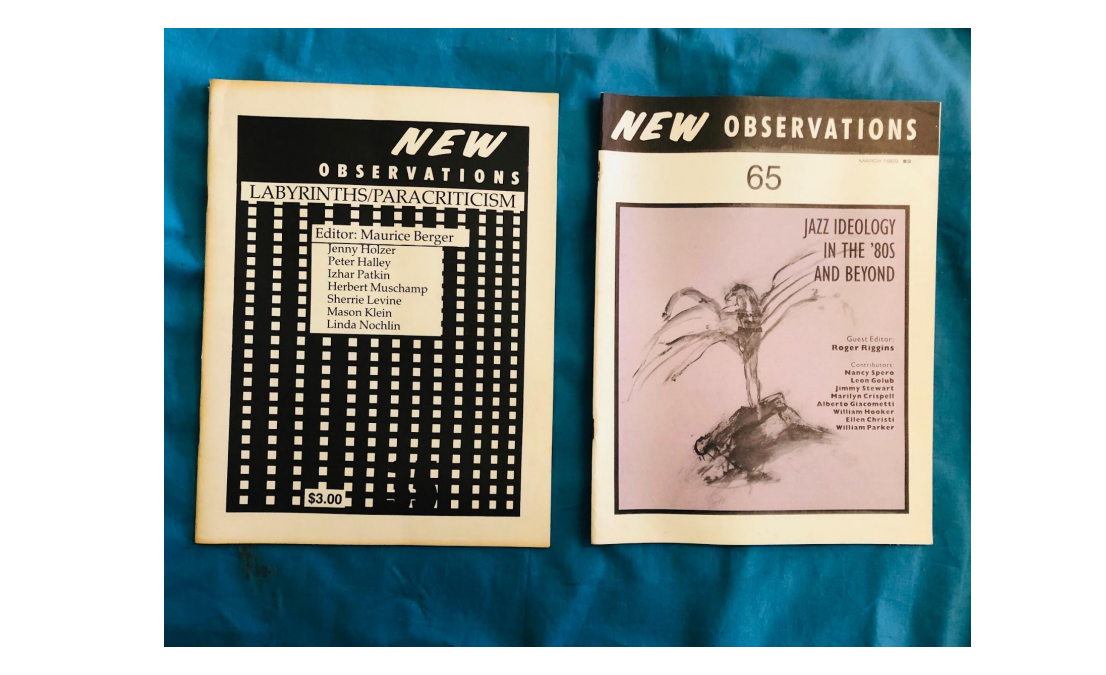

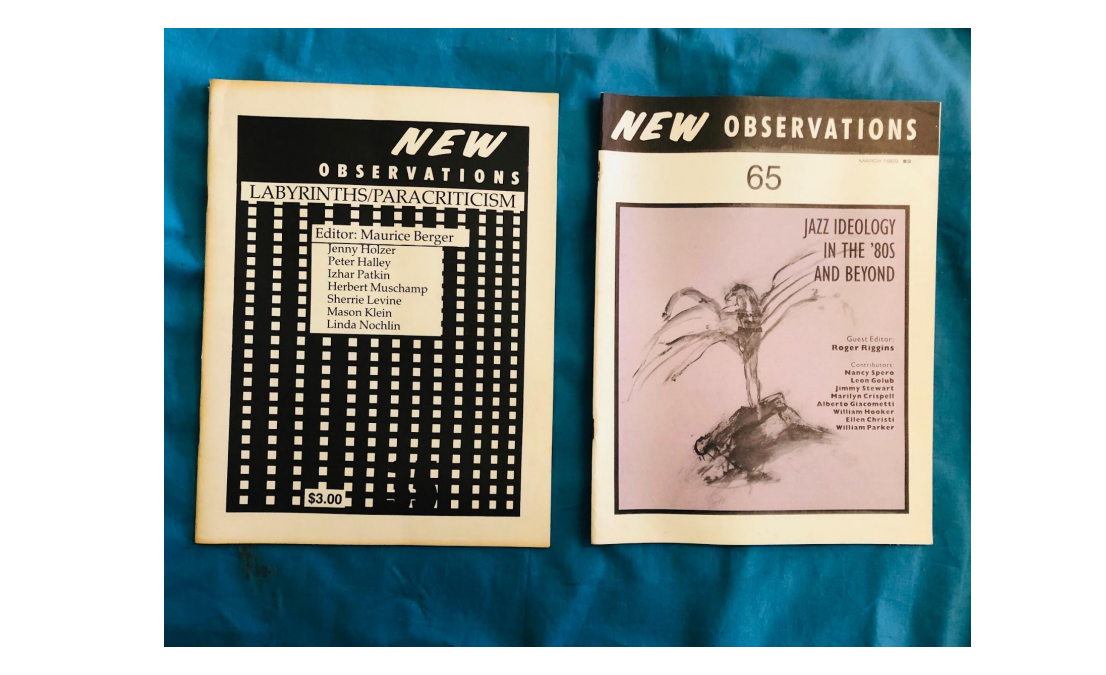

Wonderful. Shall we go to the next image? This is an aspect of your career

which many people don't realize was very important: you were the publisher

of New Observations magazine. And it was a platform for young writers, and

also established writers and artists, too. Can you describe what your endeavor

was here in the publishing world? And how you got there?

Sure. I've always been attracted by criticism, the critical outlook and at one point I

was teaching in Princeton. I had been invited there by a recommendation of Jeremy

Gilbert-Rolfe. Being in Princeton, I told Jeremy “There’s all kinds of printing

devices here, why don't we publish a little ad hoc magazine while we are here?”

And, a bit later, Jeremy told me that Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michaelson were

thinking of leaving Artforum and maybe they could join us in this venture. So,

somehow, I found myself unknowingly being the founder of October Magazine.

We had various meetings and tried to understand how to incorporate it. But before

it opened, I realized that the magazine was going to be a scholarly endeavor that I

could not commit my full time to. Annette Michaelson named it October, and I

designed the magazine with its big number and designed also the typography, and

the Princeton student Charles White went on to define it, and defined it quite

marvelously. I left the magazine because I felt it was too much for me to handle,

but I could not resist the temptation of going on doing some publishing.

At the time my studio activity was very, very heavy, I was having shows

everywhere in the mid 70s and I could not handle everything I wanted to do. But I

did want to do something in publishing also, it's like the artist coming out of his or

her ivory tower and doing collaborative work with other artists, or other writers,

other creative people. My idea was to get something in a spontaneous manner, in a

way that could not take too much time. One of the people who were working

helping me in the studio, one of these people was Betsy Sussler, who after having

worked with my studio started her own magazine called Bomb, and Betsy helped

me in gathering other people to participate in what I called New Observations. New

Observations was my answer to the more scholarly publications like October

magazine. I called it Observations because it was the most banal title I could give it

and New because everything has to be “new” in our world, as we know from our

supermarkets. So it was a kind of ironic title, it had to do with observing and also

having to be new, whatever that meant.

But you were able to get some very influential people involved, like here

Maurice Berger. I think this issue is from 1984 or 1985, and then on the right,

1989. So, you were able to bring on board a lot of, you know, influential

writers and critics.

As with my art there was panic and excitement and improvisation. I would meet

someone who seemed to be an interesting person or with whom I would have an

interesting conversation and would ask them to produce a magazine as fast as they

could, in order not to have too much self-consciousness seep into it. I would give

them two weeks and often many of them would panic. My idea was that anyone

who knows anyone else shares in an ideology and an aesthetic and a way of

thinking that is inevitable. And I felt that by pressuring people to work fast, they

would catch and I would catch a moment, a passing moment in the culture that I

was part of in New York and the States and also internationally. So, without my

even knowing, people invited artists who then revealed themselves or writers who

revealed themselves as being extremely influential, but often I did not know them

myself. Like here, you see some names, like Herbert Muschamp whom I had never

met before; Sherrie Levine I had never met. I met them after, and this was very

much part of my way of seeing art. I want art and art culture to somehow come

down from the pedestal. I like it to be a living event, both for me and the artists, for

the writers, and especially for the spectators and the readers. I don't like to impose

what we do on people, I like it to be a bridge for all kinds of different

interpretations, and I call them creative misunderstandings because the spectator

now has achieved an autonomy which he or she never had before in the history of

art. I want to cultivate this, and I started already then in the 70s, already actually in

the 60s, I started cultivating an understanding of what this could mean. Of course,

it was like walking in fog and not knowing exactly what would come. The results

have been, so far, the good seeds for what I'm doing and possibly what other

people might like to do also.

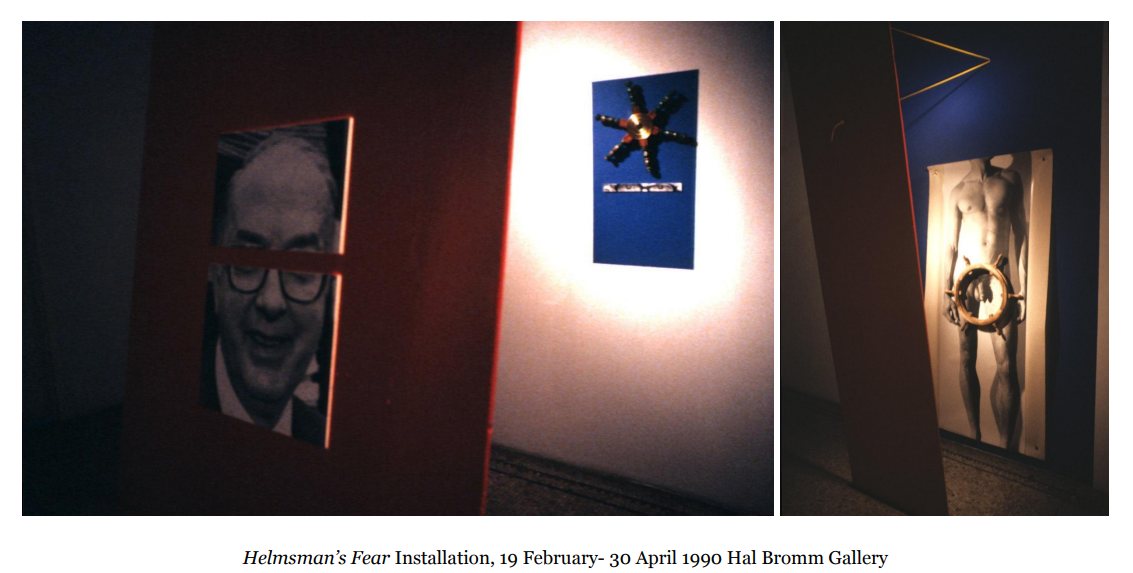

Great that's wonderful! Let's go to the next image. So, here..

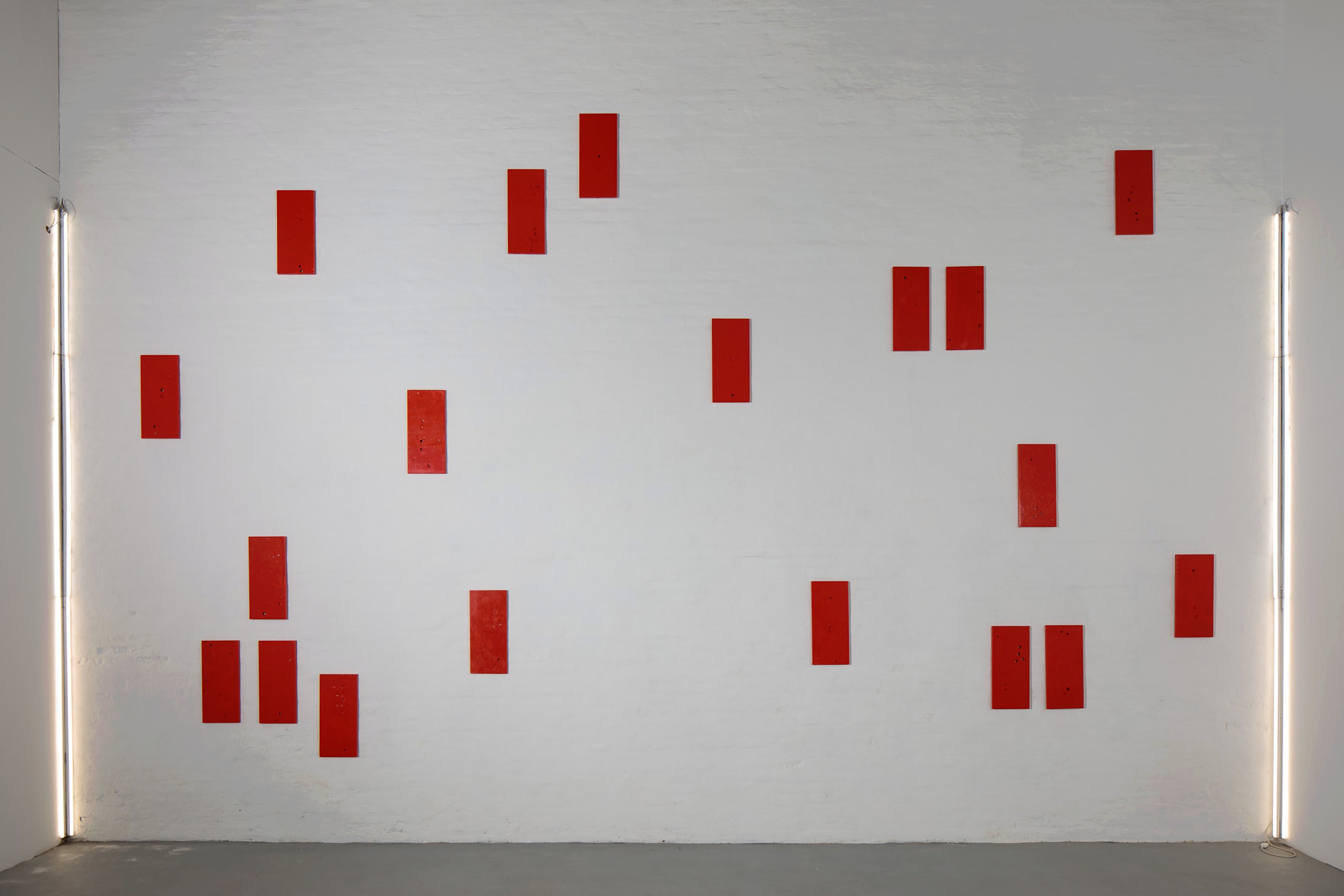

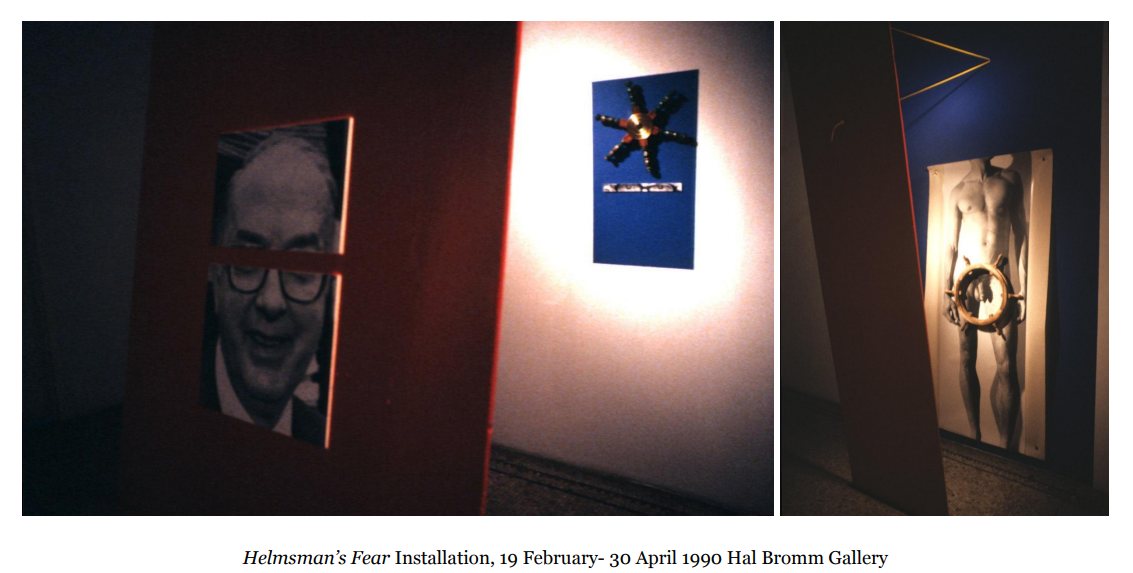

…we have another Relocation. This was at the Hal Bromm Gallery, it was called

Helmsman's Fear. The senator Jesse Helms, whom you see in this photograph with

his eyes removed, was particularly angry about shows of Robert Mapplethorpe and

what was his name... The Chilean photographer who showed at Paula Cooper he

showed... Serrano? Andres Serrano. So, I, again with ambiguity, I answered his

polemics by making this piece in which his portrait had the eyes removed. The

eyes originally were in front of the genitals of models standing in a David of

Michelangelo pose and like the David of Michelangelo had the genitals in view,

and the genitals were framed by the helm and the removed eyes of the senator were

placed behind the big red slab, that was hanging from the ceiling. (10)

Another mechanism that acted here besides removal and relocation was the four

colors, the four primary colors that I like to use, yellow, green, and blue, and red,

and which help me to do all kinds of situations in one way or another.

What was the reaction to this exhibition?

Well, many people saw the exhibition. The New York Times wrote a review of

three lines saying I was making fun of senator Helms but my friend the painter

Frank Moore took one of the parts of the diptych and exhibited it in a group show

at Lincoln Center. I was traveling in Europe at the time, and when I came back I

saw my piece reproduced full page in the Village Voice with the title "Censorship

at Lincoln Center". Somehow there had been a meeting of some kind of religious

group and some janitor thought it would be better to shroud with a black canvas the

genitals of the photograph of the model. So that was one of the reactions.

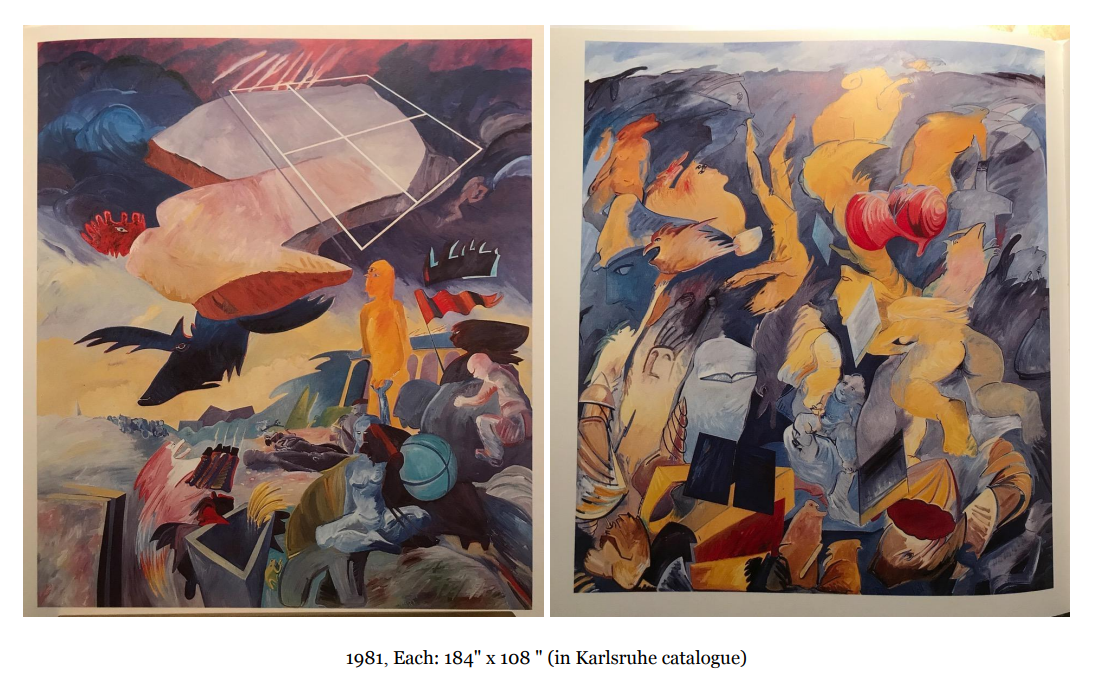

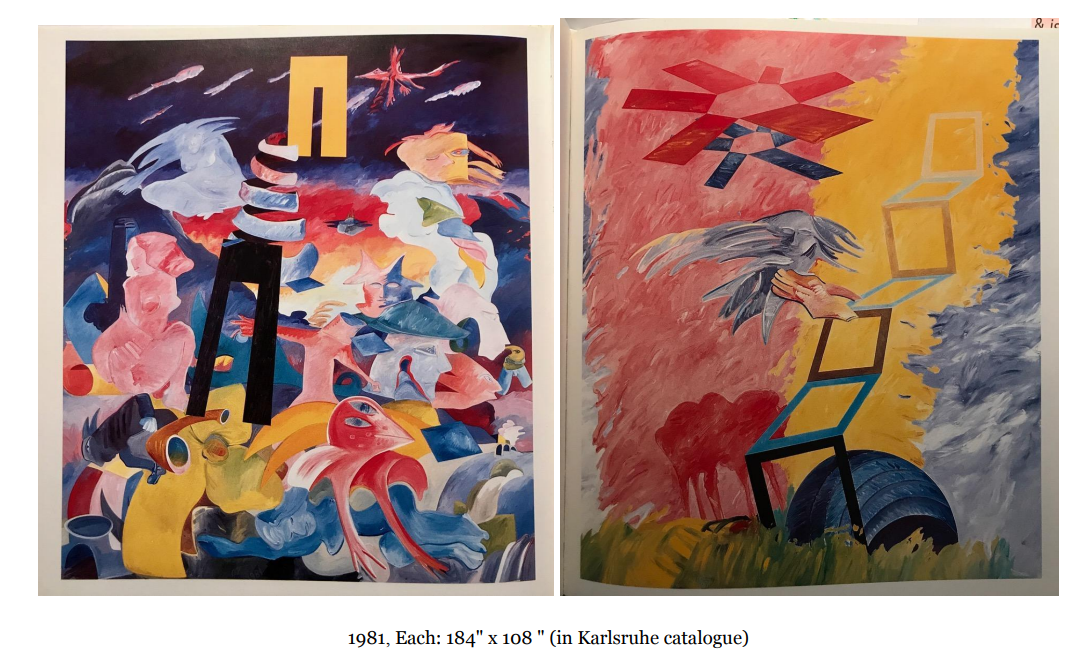

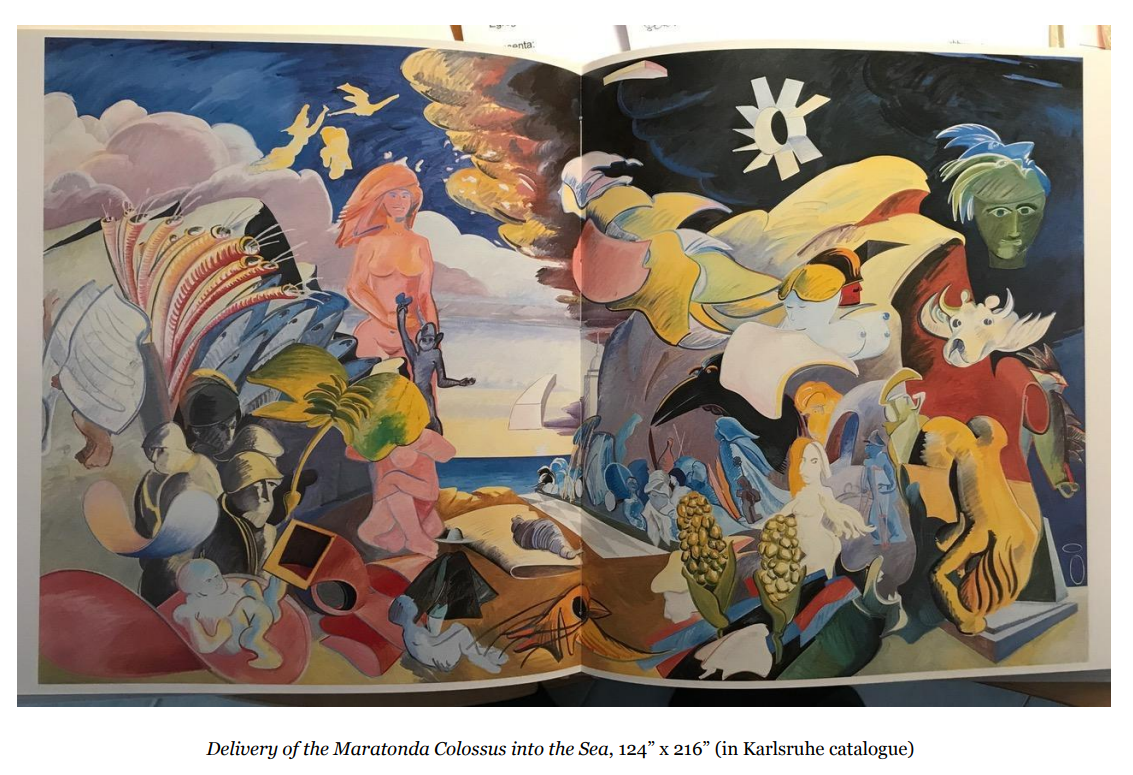

Wow! That's extreme. Should we go to the next? These were among your first

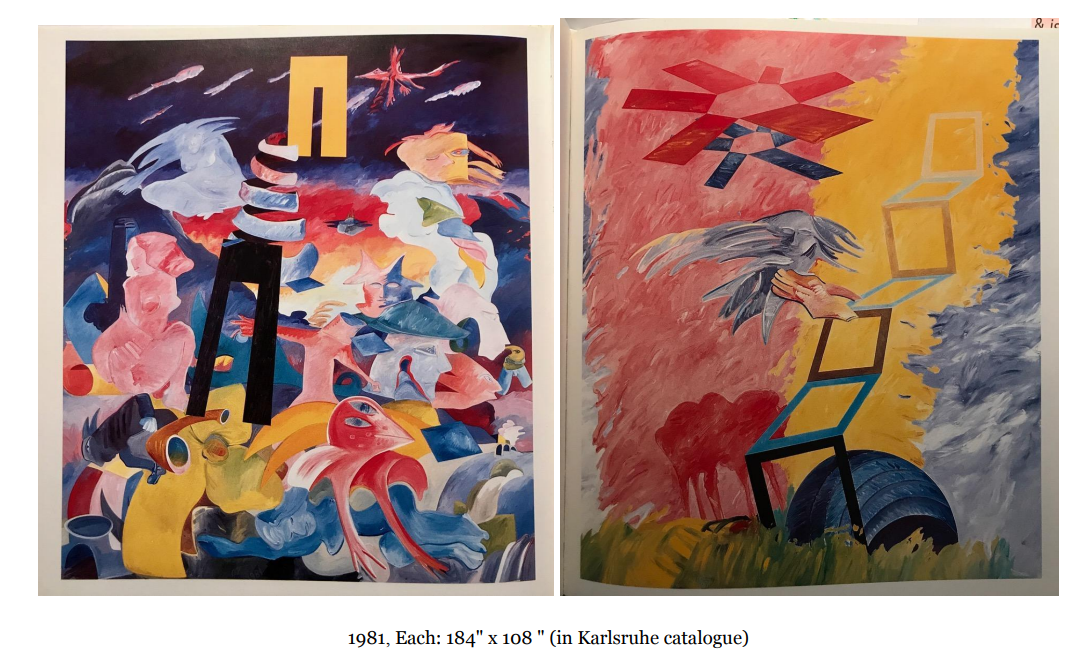

very large scale paintings at the time. They're mural size aren't they?

Yes.

You were incorporating some of your earlier works in these compositions. Can

you talk about these a little?

Exactly. This is my way of having everything intersect. My work is like a network

of strands, logical and visual strands that keep intersecting. And by zooming in and

out of different imaginary realities, they can reappear and disappear and be

transformed. In this case, in the panel on the right you can see a quotation, a quote,

of my Level Group diptychs with vertical and horizontal brush strokes, that are

installed, normally, on an empty wall. In this case they float like two rectangles in

an imaginary scene full of potential symbolism and representations, but again I let

everyone interpret as they wish. On the left side you see a kind of elk that supports

a geometric figure like a kite in a cloud and then you see migration images,

soldiers from a Napoleonic war, and don't ask me why I would use this imagery

because I probably picked them at random from illustrations or memories. I see

that in both of these paintings there are soldiers: there is a soldier on the lower left

of the painting on the right that has a helmet like World War II, and on the panel on

the left there's soldiers that look like Napoleonic soldiers. But then all kinds of

other scenes happen. And, again, I prompted my imagination to produce whatever

it liked, and trying not to know ahead of time what I would represent, but trying to

have the act of painting and the mood and the intellect generate the images.

Weren't these the culminating works in a museum retrospective you had inwas it in Bielefeld, in Germany?

Yes! They were there. They were also in another retrospective I had in Detroit at

the Museum of New Art in the 90s. And it was interesting that a young man came

to me, to my one-man retrospective, and asked me how did I feel exhibiting with

all these other artists!

Well, that's a compliment for you isn't it?

I said thank you! He was very bashful about it. I said no, no it's very regular you

would think that because the art world has conditioned you to think that way. But I

am an artist - and I'm not the only one - who has tried to come out from that way of

thinking of art in terms of formulas. I think of art in terms of languages that expand

and intersect, or like a big keyboard, like a keyboard you can play two notes on

sometimes and very many other notes on other times. And, so, he left the

conversation more reassured.

And different songs too, different tunes. (11)

But these works have a kind of retrospective feel to them. Were you

consciously, you know, putting together everything that led up to this in your

career?

Yes, the Bielefeld retrospective had 400 works, very big works and very small

works and I also did a performance there. It had from small to big, from more

quote-unquote ”abstract” to more quote-unquote “figurative”, and it had the whole

array. When, after the retrospective, which was particularly well received in

Germany, it was in a Philip Johnson building and my show occupied it all, the

works came back I told John Weber why could we not arrange an exhibition of the

same kind, maybe with not 400 works, maybe less works, in New York? So, he

gathered Susan Caldwell and Leo Castelli galleries and himself to exhibit a very

diversified exhibition of my work. The reaction in New York was particularly

negative. People thought that John Weber and I had lost our mind, and Leo Castelli

also and Susan Caldwell, of course.

What was your relationship to the Transavantgarde movement in Italy at this

time?

By the time I came to New York in 1961, no 1962, sorry, I was trying to leave Italy

and its historicism behind, for it not to condition me too much. Even though there's

no way anyone can forget one's past. In my background, I had both the Baroque

paintings that I saw in the churches I was made to frequent, and also the

avant-garde. And by living in Rome, I'd been in touch with whatever was

happening in many fields. Kounellis was an acquaintance and, as I told you, I

visited Twombly. But, from the very beginning, I must say, I began to develop a

kind of distance from the concept of avant-garde. (12)

I somehow distanced myself from any formula, any labeling. And when I was

labeled a conceptual painter, I did not like it. When I was labeled an avant-garde

artist, I did not like it. I think that our times have gone far beyond such Manichaean

distinctions and we're not realizing how far beyond that we are. I see young artists

are intuitively understanding this much more than my generation.

Why do you think that's the case?

I don't know, maybe they're just fed up with formulas, or maybe they're--some of

them--fed up with having to produce a reliable product that's recognizable. But

very many younger artists I see all over the world don't give a damn about

classifications anymore, and that I'm really happy with. I suffered through the

difficulties of getting rid of, of divesting from the strictures I inherited; but they

seem to be doing it naturally. They hop from making cybernetic, digital art, to

making paintings painted by hand, and sometimes they do theater, they do

pantomimes, sometimes they do this painting or that painting, and I'm elated by

this! Even though I don't always like what they do, I'm elated by the methodology

that they follow, instinctively, probably.

You were far ahead of your time.

Well I didn't try to, but I know that the straight jacket of my times, I could not fit

in. And, so, in order to survive I've tried other ways.

Hal: Lucio at one point you told me that a critic said to you, I believe it was a

critic, said to you: why don't you find a style? Do you remember that?

Oh many of them have told me that. And many have told me “You need to develop

name recognition or product recognition or both”. So, I answered that in 1975 with

a kind of absurdist panel on paper which I called "Oh God Make Me Find a Style"

which is an echo of Janice Joplin's "Oh Lord, won’t you buy me a

Mercedes-Benz." That was my answer. The panel continued with ‘I can't find a

style, how can I find a style’. Whatever. You know, the style is a capitalist

invention. It started around the 15th century and has lasted ‘til now. I do have

enormous respect for artists who want to concentrate on one single small realm

which in their hands becomes enormous, (13) but I don't want to be dismissed for

not having a style, because I do have a style. When people begin to look at my

work more and more they recognize the inevitability of my personal calligraphy

and my eye and my taste. There's nothing I can do about it. We cannot avoid it.

Can we look at more work?

Yes, let's look at work.

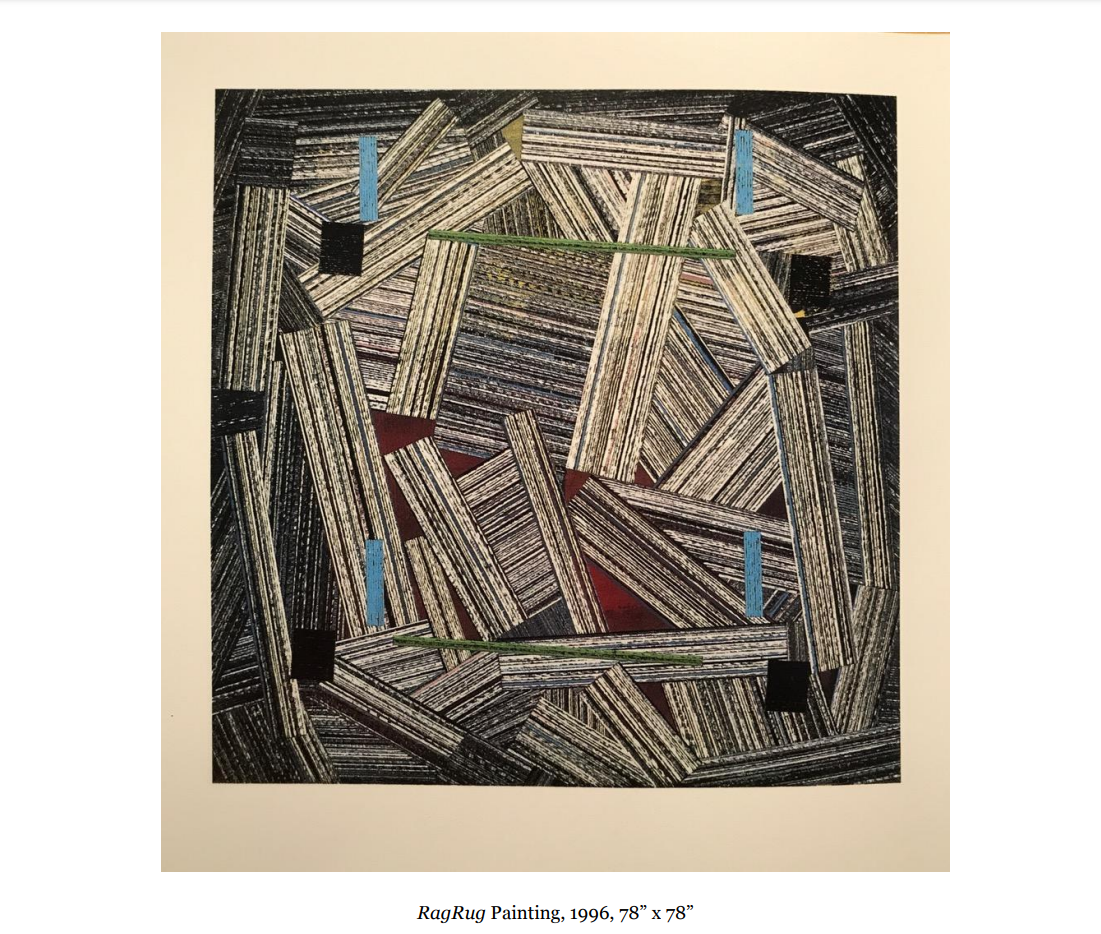

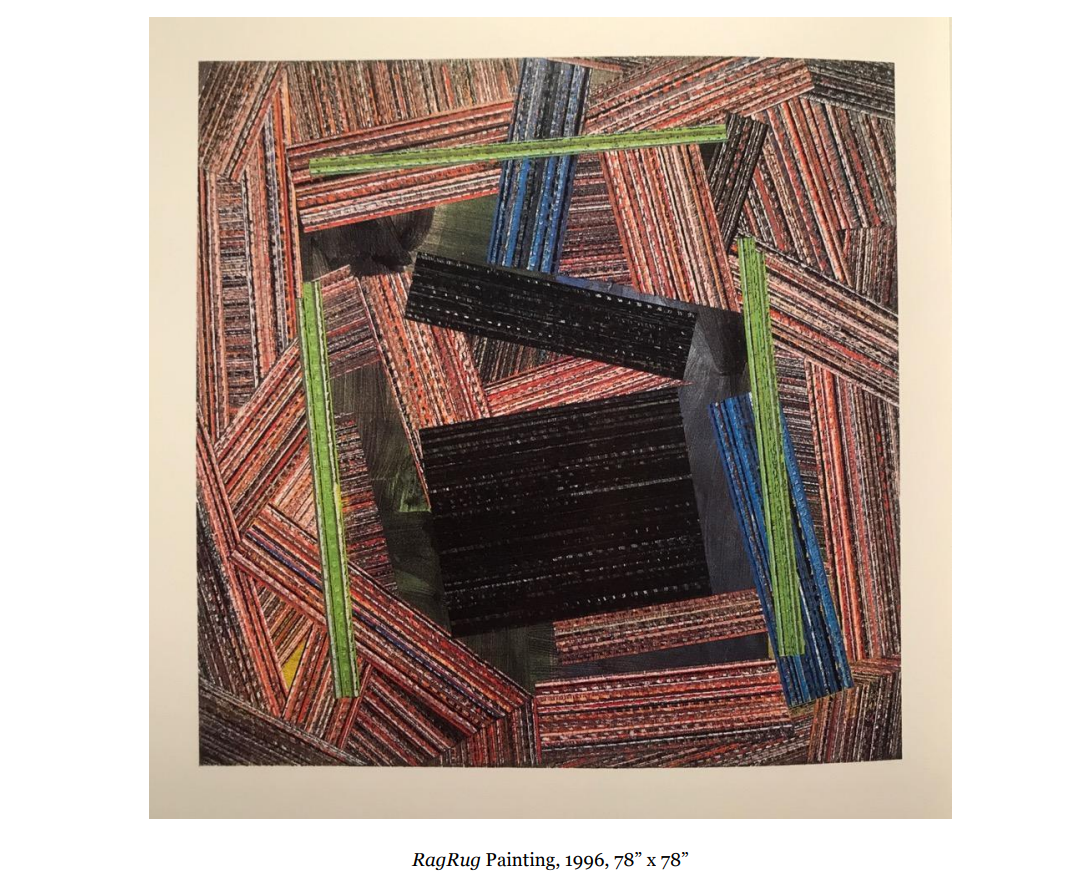

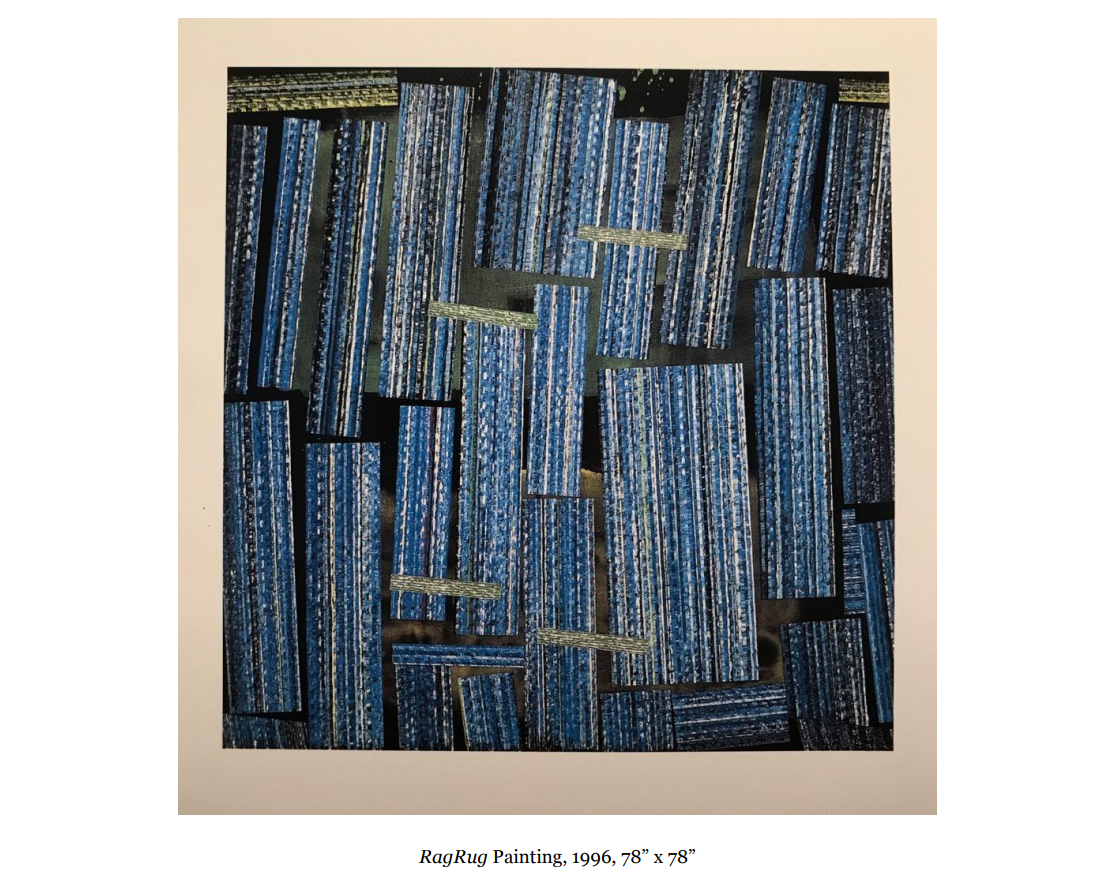

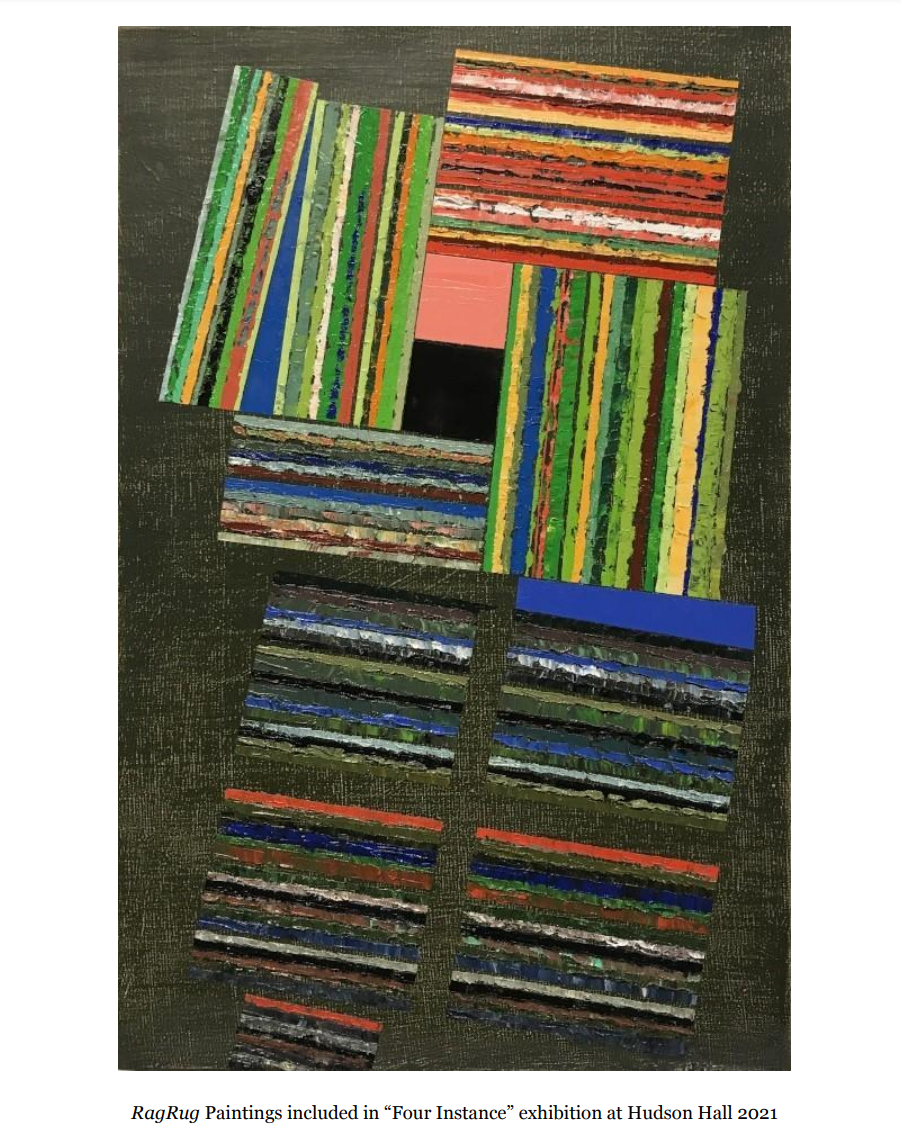

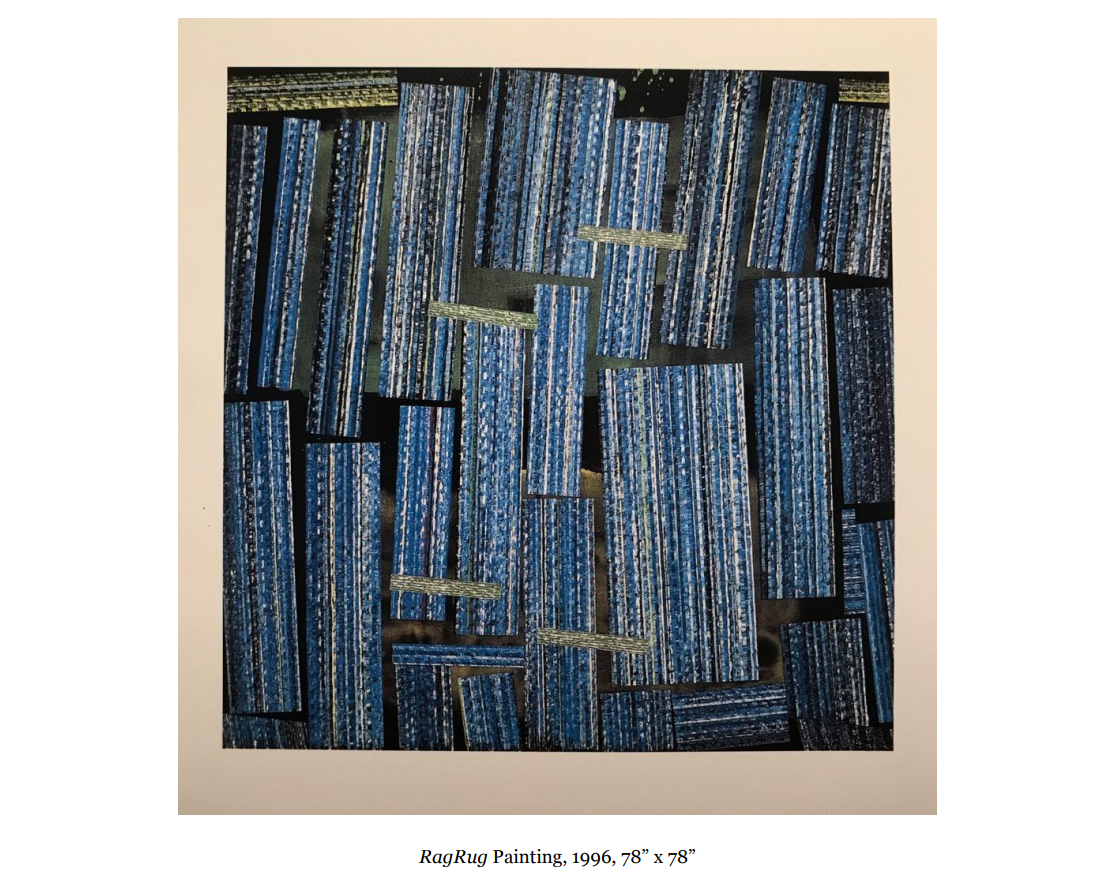

Oh what about these? These are called Rag Rug paintings that you're doing

today, you're continuing these now. What is this process?

It started with me not wanting to throw paint away. They are a kind of mosaic

alignments, palette knife-applied oil paint alignments, and I improvise. As always,

I don't know what the end result will be, but somehow I do manage to give myself

a more restrictive theme. Like in these: there was a reddish motif in the painting on

the left and a whitish motif on the one at right. I call them Rag Rug paintings

because they started by my using leftover paint from paint that had been mixed for

other paintings. For instance, when I was doing the one behind me, I also did a Rag

Rug painting with its paint. Instead of throwing it away I applied it on a small

canvas, which is somewhere, I don't know where it is now, maybe it's not finished

even. The Rag Rug paintings have become a technique that allows me to make all

kinds of inventions in different ways, and you find motifs in them that return in

other paintings as well.

How much of these are improvised? Do you start out with a plan or...?

These are big ones. The only plans I had in these was to try to have a background

of dark washes (a reviewer once called it a Rothko-ish background) and then to

apply on top of it the rectangular fields of mixed paint alignments. In this case

below for instance, bluish mixed paint. I improvise completely, every alignment,

every line is improvised. I never know exactly how it will go, and I play around,

and there's always panic and excitement at the end. In this case, though, you see

those greenish bars that are horizontal, there are four greenish bars, for them, the

canvas was taped ahead of my doing the alignments over the ground. The tapes

were removed only at the end, after I’d done the whole field with blue, and I

decided what color to put in and I did these other alignments of greenish paint.

Sometimes, I take the palette knife instead and fill a gap with flat paint. It's never

planned and I never know exactly how it will end, and I never know if what I did

was quote unquote “right” or “wrong”, because those are dimensions that maybe

are obsolete. I think that I in my painting and many painters in theirs never know

exactly when something is finished, and never know exactly what it might mean. I

never know exactly if I did right or wrong, but once it's it's done, it's done!

Well, I think Larry Poons told me once that the art of painting is knowing

when to stop. And when do you know that this composition is finished?

Yes, that's very correct. It's my problem-- I never know when to stop.

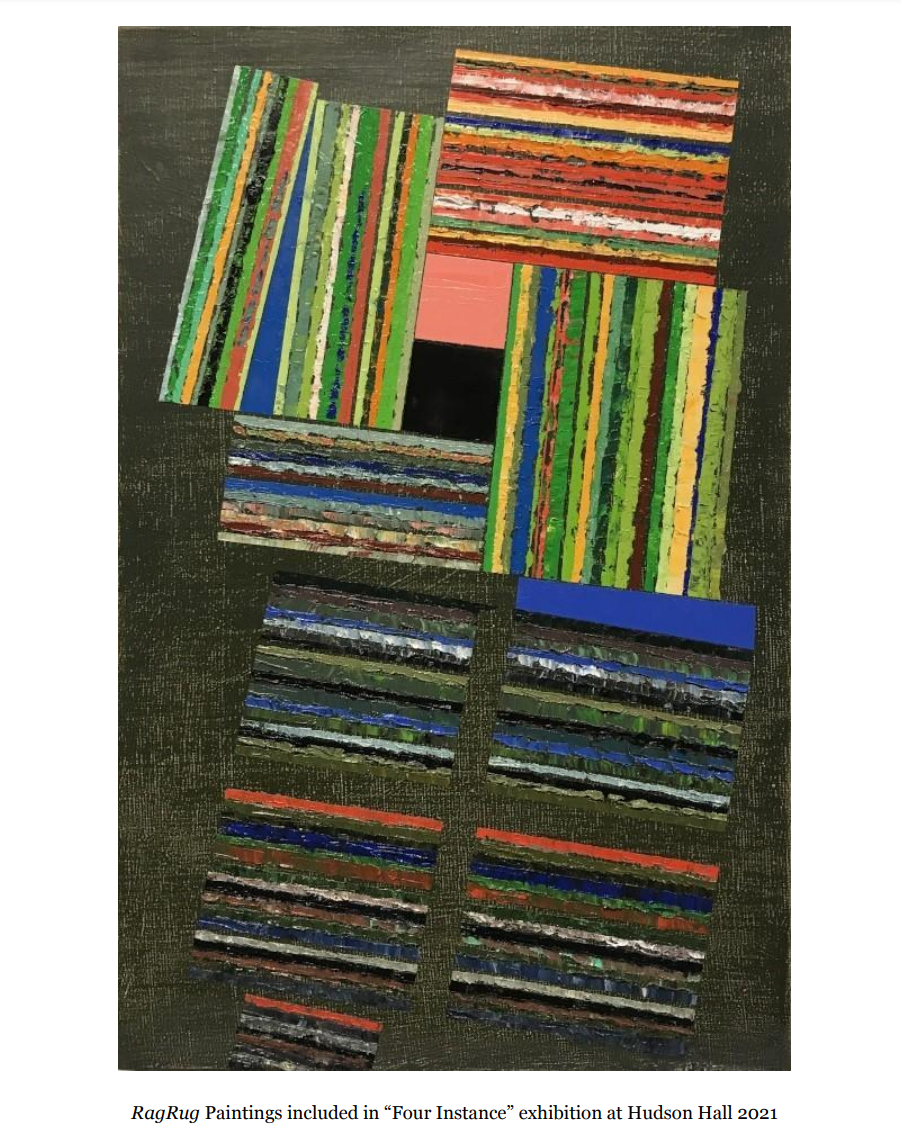

But this has a very deliberate - can we look at a couple more of these? Because

the compositions seem very tight and very deliberate . . .Aren't there ones you

showed in Hudson recently coming up? Oh they're gone. Oh this one, other

images, more images. So in this one, how much is improvised and how much

was calculated? And when did you know this was finished?

I did not know. I really torture myself. Something very funny happens: often

visitors come to my studio when I have started a painting. I start with a wash of

some paint. Like Picasso, I think of every painting as being finished from the first

brush stroke onwards. So, many times visitors tell me “stop!”. Occasionally a

visitor tells me I must push it further. But I never know, I never know. In this case,

I put the pink and the black squares first, and then I started following around and

see what happens. I never knew what would happen and I do really sincerely suffer

this. I'm not joking, it's - uh sometimes I don't sleep at night wondering whether I

should add something or not. And when I... sometimes I even mix paint to add

something, and then like a glass wall is erected in front of me and I cannot

approach the painting anymore and add anything.

But there was a painting that was even reproduced in Artforum about a show I did

at the Julian Pretto Gallery many, many years ago, it must have been in the 90s.

There are four gigantic panels in a quadriptych: one red, one blue, one yellow, one

green. For the blue one I had specified to myself I would put a black square in it.

The square had been outlined by tape leaving the white priming to be filled but I

showed it instead with the white square unfilled because I was not able to make

myself put the black in. It was exhibited many times. Then, when this quadriptych

came back to the studio in the middle of the 2000s from an exhibition, I told

myself that actually the black square should be there. So, I added the black square

and now the painting is not what it was reproduced as. It is historically reproduced

with a white square instead it has a black square. And I don't know if I did the right

thing. I don't know if it is interesting. (14)

Well, if it's right for you that's the answer.

Yes,

and shall we look at some more installation works coming up. Just briefly talk

about Kingdom?

This was at the center called CR-10 in Hudson, New York. It's a gigantic space,

and the space generated the idea.

I worked with Judy Pfaff on a show there but (I don't know how) I missed

this show of yours. Was there a performance with this exhibition?

Yes, I did, during the exhibition, in another room of the center, I did a performance

in which I spoke an imaginary language called 'Patchameena,' which is the name

that my autistic brother had given to our playful language while we were playing as

kids. (15) 'Patchameena' is nonsensical gibberish, but it indicates that the meaning

in art is always escaping between the two extremes of sense and nonsense. So, in

this case there was upstairs this installation that was maybe more sensical, and

downstairs I did a nonsensical talk accompanied by wonderful music played by

Brian Dewan a friend of the director of that space, the artist Francine McGivern.

And I alternated something that had apparent meaning with something appearing to

have no meaning, a gibberish language. [Lucio speaking Patchameena]

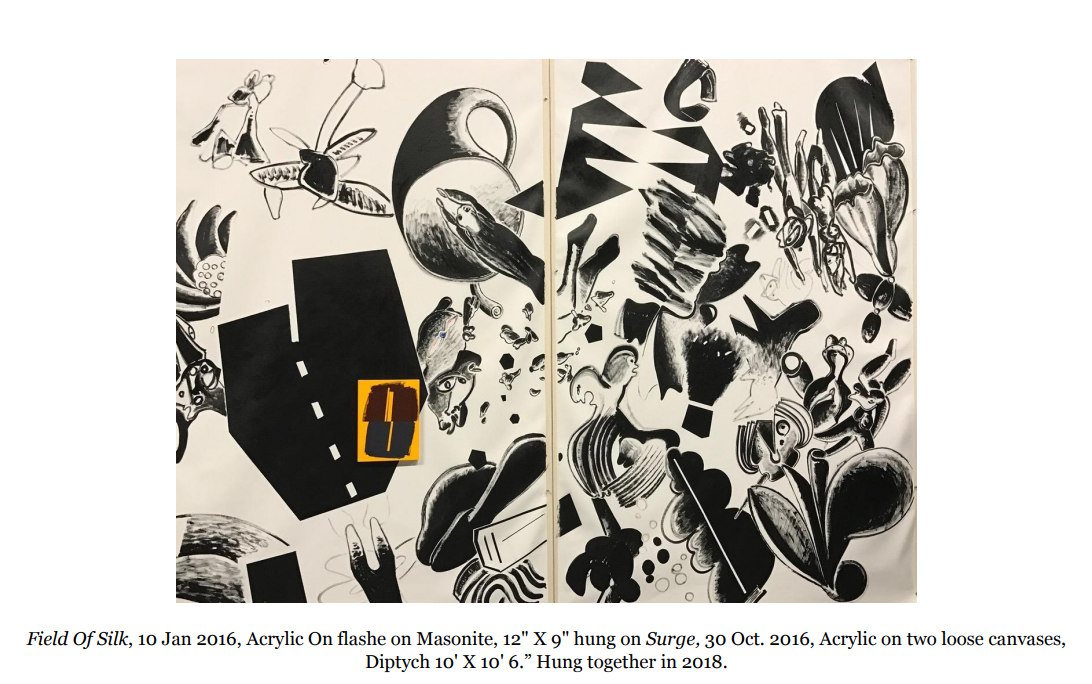

Oh. I understood that perfectly! And so this is a mural that you did where

you hung a work on top of another. That's a painting in black on white, and

the yellow and black is a Rag Rug painting, correct?

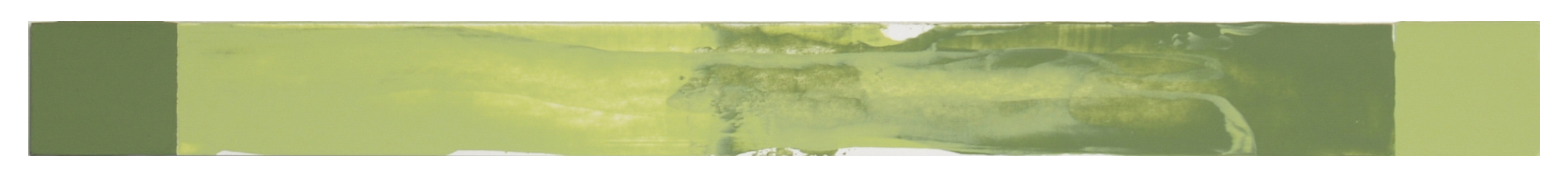

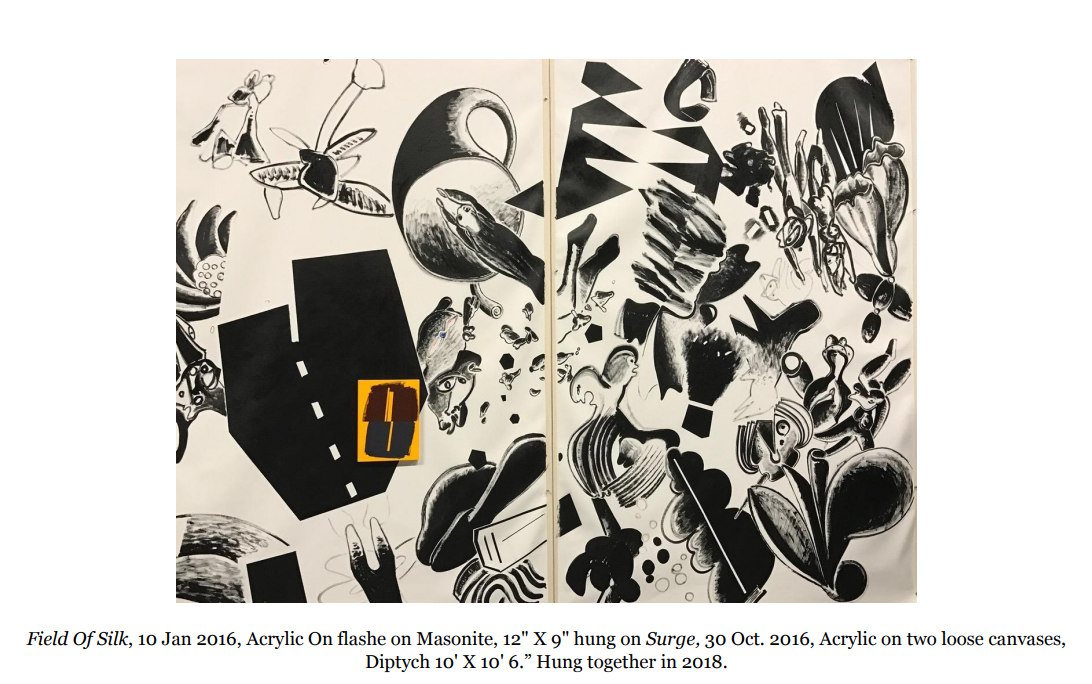

It's not a Rag Rug, it's a Dif raction painting. In this group of paintings, there's a

background painted in vinylic tempera which is matte, and over it, the paint is

acrylic which is more shiny. Two acrylic color fields are applied one after the other,

and they meet at a dividing seam, like the paintings that are now at Hal Bromm's,

and the images in them don't match. In this case, I had painted in black paint this

big, gigantic canvas diptych for a temporary exhibition. It was going to be held in

the studio of a friend of mine the late Alain Kirili, and I put a nail in the painting

and hung the small diffraction painting on it. So the painting was black and white,

and the diffraction painting has color and they all reflect one another in some

awkward way. Whatever way you want.

It's got a very eccentric elegance to it, I would say.

If you look at the left panel and the right panel of the black and white painting you

see that they continue without matching, so, for instance, you can see an especially

geometric shape that starts in white on the left and then ends in black in the right

panel. And the same mismatching happens in the little painting with the brown on

top that has some negative lines that don't meet the negative line in the gray on the

bottom.

Wonderful! And then next is your...this is Mantua?

I had a very big show in Mantua two years ago in the museum called Palazzo

Ducale, which is the palace of the duke. The curator accepted my hanging one of

my Scatter paintings, which are big acrylic paintings, together with the baroque

17th century paintings in a room. Another room had 8 seven-yard long scrolls of

black and white paintings, like the diptych we just saw, hanging on the tensor bars

crossing the ceiling of a giant room filled with other paintings from the 17th

century. In this case, this painting matched the agitation of the classical 17th

century Italian and European paintings. I don't know who those paintings are by

but they are part of the Baroque movement. And without my knowing, somehow I

think I have...I've found myself flowing, not only in the surrealist or whatever you

want to call it abstract or realistic manners, but also something seems to have been

coming together with an echo of Baroqueness, which pleases me very much in my

desire to open up my culture, and possibly our culture, in all directions.

So, this painting, though, was not, you were not corresponding with Baroque

Art. This is your composition. It was completely by chance?

Yes, my composition was developed within the terms of a group of works that I'm

still doing called Scatter paintings. They’re acrylics. Thickly applied palette-knifed

acrylics on top of loose backgrounds. And when the big exhibition at Palazzo

Ducale was offered, I felt it was interesting to place this painting together with

paintings that had such difference from the past. And, yet somehow, were

connected to it formally.

Well because of the arms, the black forms look like arms or something.

I would say the agitation. If you look at the zigzagging of shapes, I feel there's

some echo...The movement. An unintentional echo.

Definitely, yes. The next please.

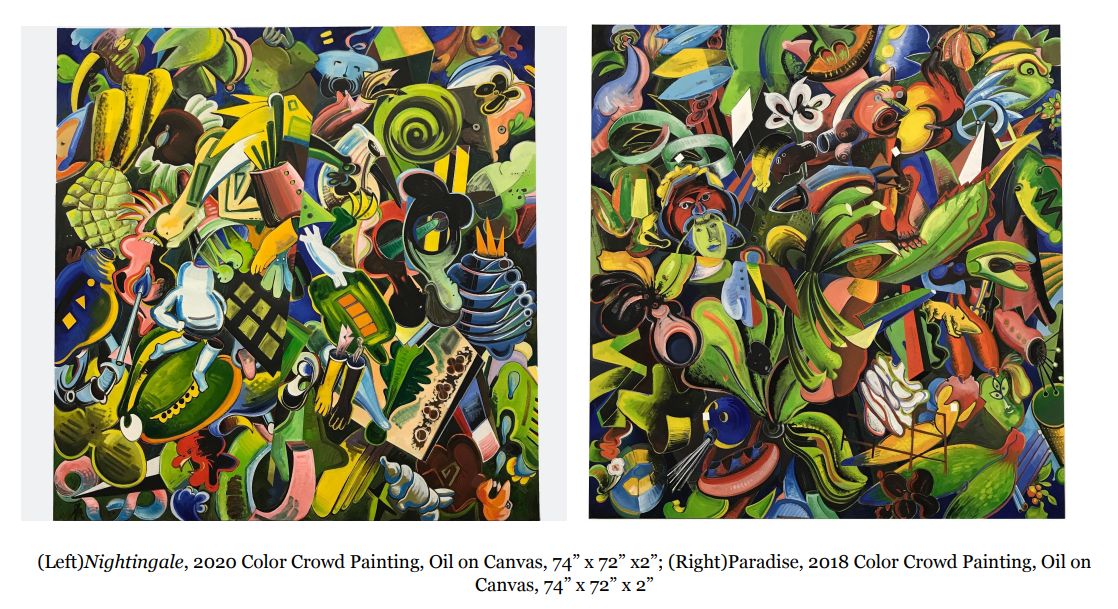

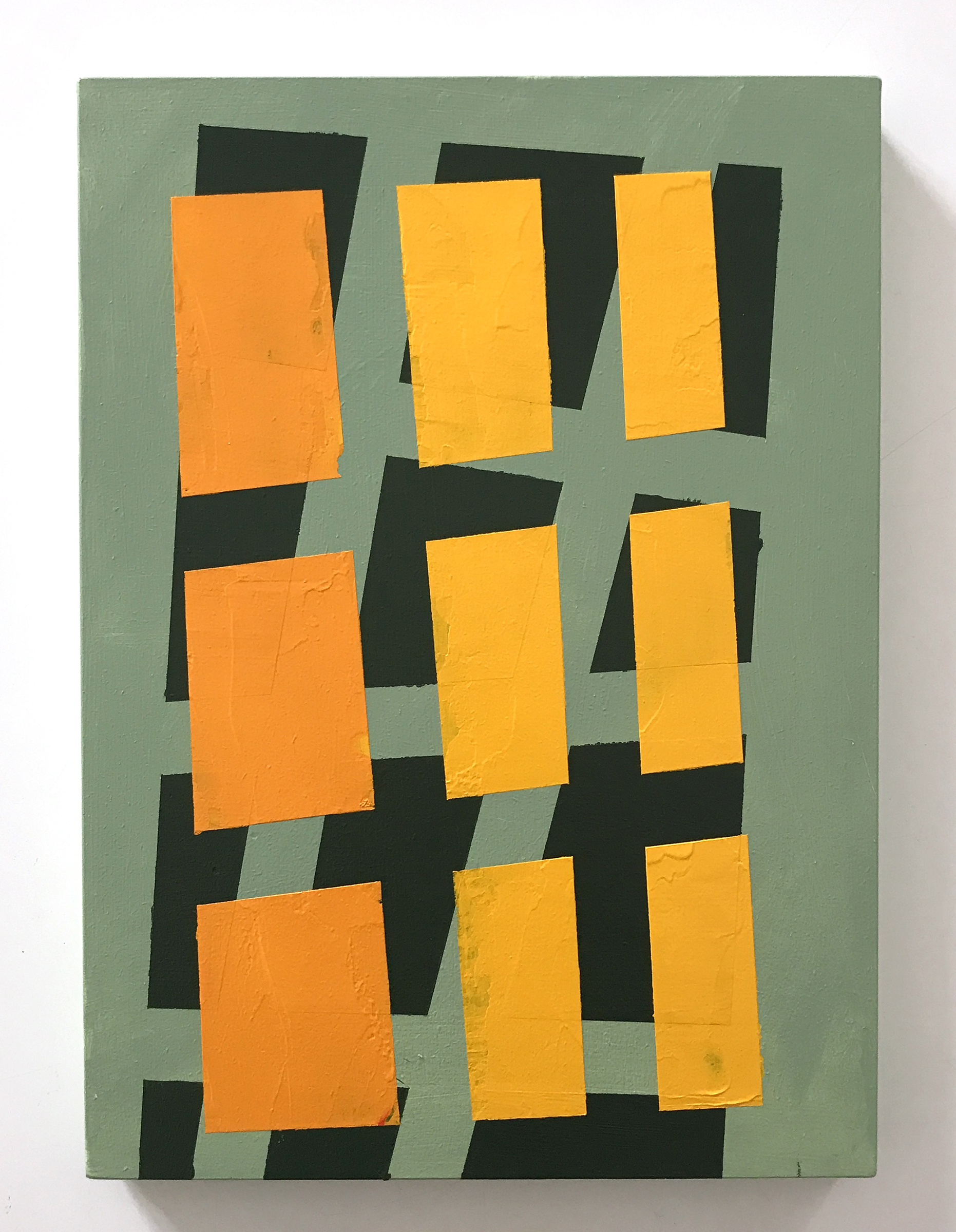

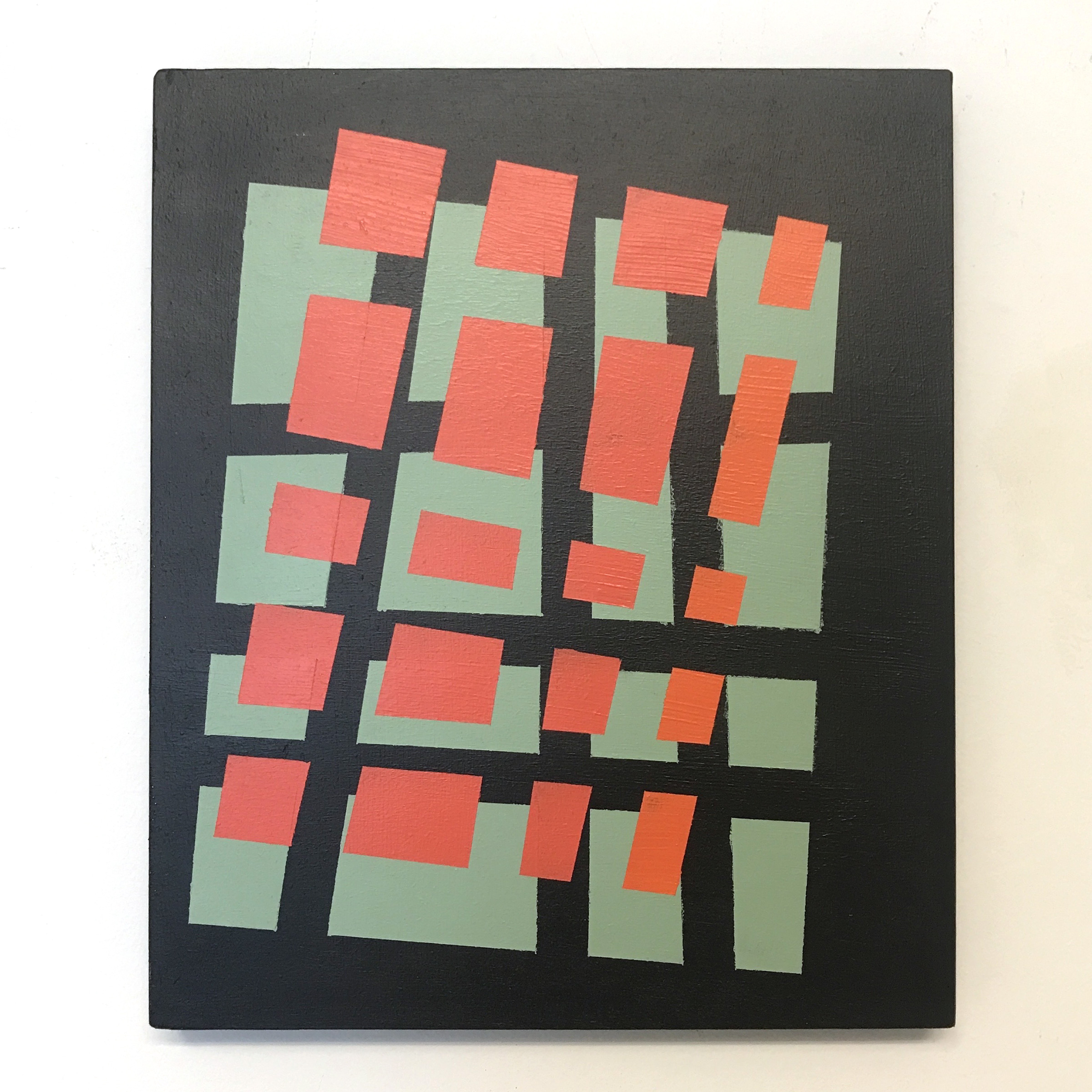

These are in the exhibition? The current Hal Bromm exhibition?

They're in this exhibition now at Hal Bromm's. And if you look carefully, you see

there is a vertical seam in one and a horizontal in the other at which the left or right

or upper or lower side don't match. There's a division there, there's a crowding of

shapes of all kinds and they meet without meeting on these seams. I painted one

half first and then the other half to respond to it.

Is there a specific placement of that division?

No. I start by feeling the horizontal and the vertical divisions. Somehow they act

like translation mechanisms. They are a link that allows speaking in different

languages. It is a process similar to speaking different languages all my life.

Are you channeling Hieronymus Bosch in this, these compositions?

Oh Bosch, yes! Bosch is inevitably an echo for me, always. Bosch and Bruegel and

surrealism are an echo. (16) They pop out without my even wanting. I don't intend

it, but I let the influences in. I think there's no art that's not influenced by

something. So, I let influences seep in without my wanting, without my choosing

to. You can look everywhere, you can see also Bosch here, Hieronymus Bosch.

You can see Malevich, you can see all the people I love, they come in. There's

Donald Judd somewhere, whom I don't particularly love but he pops in also

without my wanting.

I'm seeing those creatures they're...the density of their... it's all very

compressed, the composition is compressed.

Yes, it's a filling-in in this case, it's crowding in, it’s the counterpart of emptying out.

Maximalism.

Maximalism, call it maximalism, but consider that at the same time, almost the

same period, I did also the black relocation and the white relocation, that are shown

in this same show. Here they are. They were done at the same time. In order to

relieve myself from the crowding, I also uncrowded myself a little bit. And that

gave me energy to crowd again in some next thing.

Are these meditations on architecture?

The relocations, when they happen this way, become architectural. I had an

experience studying, attempting to study architecture when I was in Rome, before

coming to the States, and that influenced me radically. I conceive of every picture,

every painting, every situation I build as being architectural. Even those crowded

things, the paint of the background goes around the edge of the stretcher, and I

always think that the painting is not a painting on the wall, but is the wall activated

by the painting regardless what's on it.

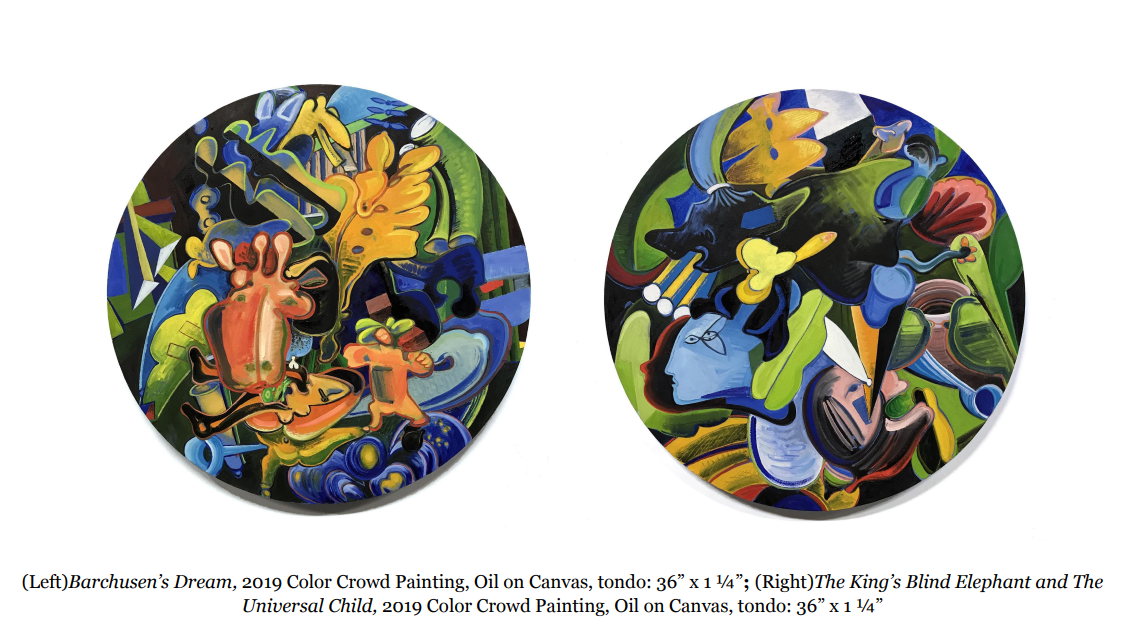

That's a wonderful statement, Is that the, is this the next ,the next image?

The tondos.

These were made at the same time as the other more complex paintings.

It's two small tondos I found in the studio, prepared long ago, before I had the

traumatic move from New York because I couldn't afford staying there anymore.

So, I have all kinds of canvases that are ready to be painted and they're wonderful

occasions to rediscover them, regardless of what the intentional preparation of

them might have been. And these are two cases in which that happened.

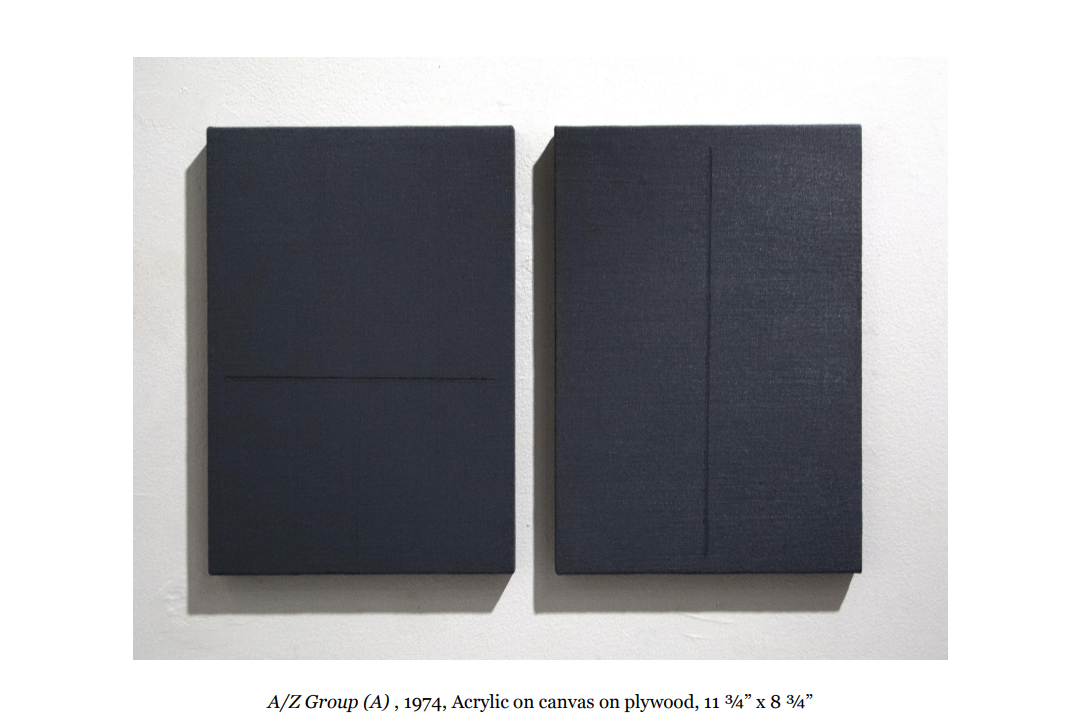

And then finally, is there one more slide of the Level Group?

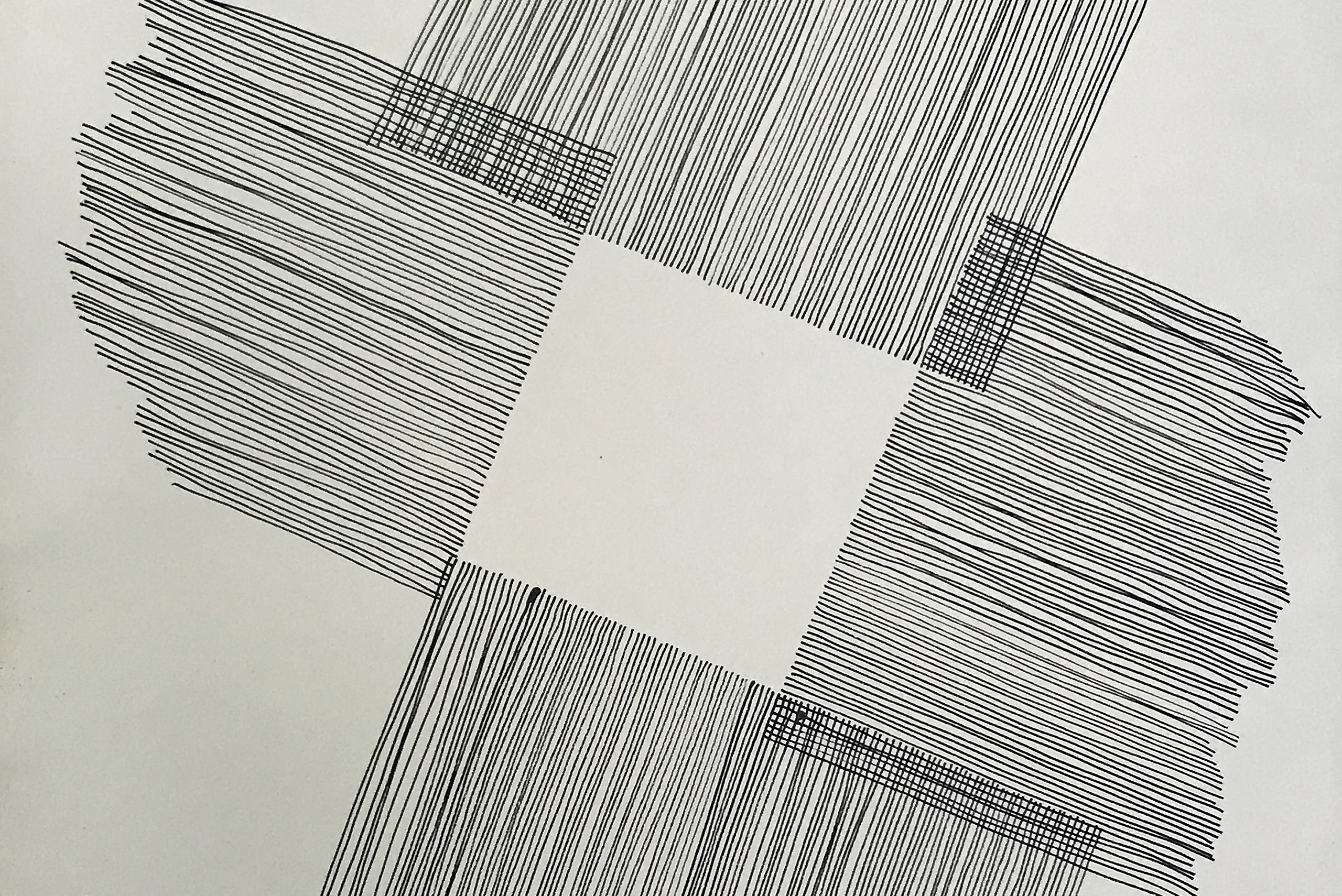

These are the original, these are even before the Level Group. These are, I call

them A/Z . I showed them first, my first show at John Weber Gallery, called Paint

Works. (17) There were two diptychs. In each, on one panel a horizontal pencil line

resulted from removing wet acrylic paint spread with vertical brushstrokes before it

dried, and on the second panel horizontal brushstrokes had a vertical removal by

pencil of the acrylic before it dried. That dualism, vertical horizontal, keeps

reproducing itself, keeps giving me occasions for doing whatever I feel like doing,

whatever comes necessary.

Some works are caused sometimes because of a spiral return of my ideas but

sometimes also as prompted by others. I published in Bomb magazine once a

diagram which was like a McDonald's menu, in which I asked people to order

paintings. And they would tell me what kind of size, what kind of imagery they

wanted. If it had to be full or empty, thick or thin, and what colors they might want.

Because the sensibility of the painting, the aesthetic and theoretical decisions, seep

themselves through the activity of the artist, far beyond his or her intentions. I was

elated when I read in the first chapter of Erwin Panofsky book Meaning in the

Visual Arts, a very important parenthesis, he says "the symbolic value of the

artwork almost never corresponds to the artist's intention".

Yes!

Hal: One question early on was who were your mentors and teachers?

My one mentor and teacher was my stepfather Michael Noble. He taught me very

many things and then I started going to studios of artists that interested me,

begging for technical and also aesthetic information. Very many, I don't know who

to name. Maybe I chose my examples. I have a high school degree which I

achieved only because my father recommended me through a friend to the

commission that was going to give me the diploma, and then I was never able to

study but I read very much about theater. When, later on, I found myself being the

sole professor of Contemporary and Modern Art and Architecture at Cooper

Union, I had to stop painting because I had to learn what I was going to teach. I

read a lot but the books I needed were not available at the Cooper Union library at

the time. I found them in the Wittenborn bookstore on Madison Avenue which was

mentored by Robert Motherwell. I found there all the books that I learned

everything I know from. So for two years, I taught history of architecture and

modern art in Cooper Union. I had to stop making art or at least reduce making art

to the utmost and I studied very much. In a certain way, I learned my trade there.

Hal: Another question is: Lucio's visual language is unlimited, might he say

something about the variety of mediums, forms, and approaches he has used.

Yes, well, the project, I did set a project for myself. The way that I have, that I've

lived in it has grown into me without even intending it too pedantically, the way

that it has grown into me has no end. There's no conclusion. One thing I discovered

recently, really two three years ago only, was that the modernists, the modernist

artists in the avant-garde movement in Europe and America, were all trying to do

something that the market is still trying to do: to conclude, to find final solutions.

And I realized that their enemies, the regimes of the Communist and Fascist all

tried to find final solutions. So when people try to have me conclude, to pin me

down into a final solution, I immediately get terrified of this disease of modernity

coming back into me, or in discourse. I'm terrified of them trying to lock me in like

the modernists and all the evil political movements have tried to do, and the

discriminatory movements of any kind, even now. So I beg them to not try to pin

me down; not try to close me in anything. I'm an open event, like many others I

will never conclude what I'm doing. My art, my artworks come from all kinds of

influences that are all very healthy because they are discourse with the past, and

the present also, influences are welcome and you cannot, I cannot pin myself down

in any intention or any conclusion because I really want not to know. As I wrote in

a letter published in Artforum in the 80s, a letter addressed to an art dealer called

Peder Bonnier, "I want not to know what I want."

That's beautiful Lucio. Thank you! That seems an appropriate way to close,

don't you think so Hal?

Hal: Absolutely. Thank you both very much, it's been a wonderful conversation

and we're getting a lot of people on the chat saying how much they've enjoyed it,

which is terrific.

Oh great. I have too Lucio! Thank you for your generosity and for sharing

your thoughts with us today!

But I'm the one who thanks for being prompted in all this and of course I'm going

to go have dinner now because it's dinner time, wondering how badly I've

expressed myself and all the things I've missed out, but thank you for prompting

me!

It was brilliant, brilliant! Grazie!

Hal: Thank you all for joining us today and this evening and uh we'll see you

next time! ciao!

Ciao!

Annotations :

(1)

Galleria dell’Ariete, owned by Beatrice Monti, was one of the probing galleries in

Europe. Besides exhibiting New Yorkers Robert Rauschenberg and Susaku

Arakawa, and other Americans like Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Kenneth Noland, Cy

Twombly, it also presented a strong group of international Italians, like Lucio

Fontana, Piero Dorazio, Enrico Castellani, Giulio Paolini.

(2)

I was exhibiting monochrome red paintings of different shapes placed on the walls

in various manners, and I thought actions representing diverse levels of interaction

with the viewers could complement them.

One was Shootout #1, which was interrupted by the police. Having lost because of

that the loan of the storefront I was using next to the gallery, I continued in the

gallery’s courtyard. There was Questionnaire (visitors would fill forms about Art,

Love, Politics, Nature), Painting to Order (having set up a kind of pantry of

ingredients on a table, for eight hours I painted only in red on small papers

fulfilling orders written by visitors on a supplied order form), Pools of Water (four

inverted plastic skylights filled with water tinted in Red dye) which never was

made.

(3)

Joan Jonas and Simone Forti came to see Paperswim at DIA.

(4)

In Milan and at Tyler visitors came in and out and found a giant pile of paper

tapering down towards them, like a dune ending in a beach at the water. When I see

a child approaching the edge, I crawl within reach of her feet and design a mark

just for her, which normally pleases her very much.

We artists are often worried about our art’s accessibility. Sometimes I fear I might

be too hermetic and elitist, but while I was performing at Tyler suddenly the lights

became very strong and from under my paper I wondered what was happening. TV

had rushed to see and I found myself on prime time news.

At DIA in 1991, they set up three rows of descending stadium benches that viewers

returned to when they wished.

(5)

I wish a study in depth could be undergone of Pink Eye.

It’s a piece dense with references to the history of art and to history. There are

innumerable possible interpretations of it, not all pleasant ones, and a viewer could

unleash its imagination in developing from it so many narratives.

The photo-portraits of pacifist and leftist leaders of the XXth Century, mounted on

board, are aligned at ankle height at the bottom of a wall. There is nothing

secretive about them as each face is historically iconic.

From left, Salvador Allende, Patrice Lumumba, Che Guevara, Vladimir Lenin,

Mohandas ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi, Fidel Castro, Karl Marx, Franz Fanon, Mao Tse

Tung, Rosa Luxemburg, Fred Hampton, Antonio Gramsci.

Many of them were assassinated. Their removed eyes were attached on the

opposite wall at exactly the same height and position of the slits left in the portraits

from their removal. A black and white photographic poster was affixed at normal

picture height to the wall above the line of eyes. A man in a suit, his right hand in

the pocket as if he were peacefully watching a performance, is observing two men

in camouflage attire beating another man with night sticks, and we, the spectators,

are walking by, secure in our spectatorial protected distance in our detached art

context.

I don’t say where and when the scene in the poster is happening because, as

presented, the scene is not anchored to a specific event but is representative of life

as it continues to happen everywhere. I am always torn by the temptation to tell

where this happened but feel that doing so would reduce the power of an image

that applies to so many events in our time. Revealing what it was would trivialize

the piece to the chronicle level of historicized reports, which, we well know,

removes them from our suffering by reducing them into merely consumable goods.

Haven’t you noticed how once you learn about some horror happening here or

there, your anxiety and compassion get quelled by it being immediately packaged

away from you in the form of News that you received and are quickly substituted

by other news good or bad?

Why leaders of peace and revolution? Why eyes looking at their roots and not at us

viewers or at the scene above them? And there is so much more about it.

As for instruments, in this case I applied the mechanisms of removal and

relocation, serial arrangement.

At that time I often bought images and the right to use them for art, paying very

little money, from the monumental United Press shelves in their storage in

Midtown Manhattan.

(6)

In order to have my works linked not by the kind of pre-decided formulas that

people call recognizable style, I have extracted from the practice of painting a few

technical, simplistic, obvious, devices that I can call upon, often but not always, in

structuring a situation, be it a painting on canvas or wood, a set of photographs or a

construction. I call these devices “Translation Mechanisms”. To mention a few:

Removal Relocation, Four Basic Colors, Serial Arrangement, Dualism, Front Back,

Up Down, Force of Gravity.

The Mechanisms are instruments. They act as frameworks that can sustain

innumerable emotions and themes.

When placing my art I consider all the circumstances of where I am operating in.

The conventional eye-level presentation is only one of the options. This

consideration of totality derives from my interest in architecture and reading about

Erwin Piscator’s concept of Total Theatre in the 20’s and the Bauhaus esthetics of

integration - already foreshadowed by the Contructivists and Futurists - which later

in New York generated the Site Specific movement I was a practitioner of, starting

with my several shows at PS1.

(7)

Here you hit at a core point of my venture. I have no interest in reconciling

anything. Under the veneer of mass society ours is truly an atomized society and I

myself, after trying to contain my life in a coherent territory, have discovered that

doing so would be hypocritical. Socially we may dialogue with one another and

find some way of coexistence, but inside our self, I feel it’s most creative to suffer

and enjoy the natural split of our thoughts and emotions. Given that there is no

agreement anymore about the aims of art, I prefer an explosion of diverse strands

rather than their reconciliation. To reconcile sounds to my ear equivalent to

homogenization, regulation, least common denominator, solution.

In 1992 Mac Chambers, director of the Grace Borgenicht Gallery in New York,

co-curated with me an exhibition I had been keen on doing: Concurrencies.

Wondering whether I was as alone, as I had been told, in my feeling restricted by

modernist marketing canons, I had discovered that in October 1921 Picasso had

painted – note: during the same month – Three Musicians and Three Women at the

Spring, two paintings that were at opposite poles from one another in style and

manner. From there, I started seeking other events of the same kind and found there

actually is a whole line of artists who within a narrow gap of time or during their

whole lifetime produce radically diverse artworks concurrently. The Borgenicht

Gallery, being a powerful institution, could borrow major works. The show

included young and old, contemporary and past: Ellsworth Kelly, Annette

Lemieux, Saint Clair Cemin, Gerhard Richter, Papo Colo, Konstantin Vialov,

Donna Moylan, William Anastasi, Dove Bradshaw, Louise Bourgeois, Lucio Pozzi,

Pablo Picasso, Robert Storr, Connie Beckley, William Wegman, Scott Grodesky,

Michail Larionov, Dorothea Tanning, Man Ray, Cindy Tower, Lucas Samaras,

Ursula Hödel, Piet Mondrian, Sherrie Levine (doing a Mondrian), each with two

works done within a short period. Mac had included Robert Storr, best known as

curator and critic, with one of his paintings and a book of his. Attached to the

catalogue was a list of many more artists. The trend of concurrent art has a long

tradition, ignored by the short-cycle market.

(8)

This question about whether I paint some landscapes sitting there in person raises

the issue of the difference between site-specificity when depiction happens by

immersion of the artist in a place (in my case it’s also an act of nostalgia for

ancient ways: foldable stool, carry-on palette, wide-rimmed hat to cut glare etc)

and the site-specificity of art placed in a site like a sponge (a definition by Royden

Rabinowich when we shared a show at John Weber) absorbing and reflecting what

is already there.

When I did the 10 Color Combinations in the PS1 inaugural show (1976 ), I was

referencing that connection not only in terms of mimesis but also in terms of there

literally being a horizon.

(9)

This watercolor was occasioned by my seeing some Jan Breughel the Younger

paintings that include extremely detailed depictions of flowers. My mental context

was thus very different from the on-site paintings.

(10)

Here is a more detailed description of Helmsman’s Fear.

This piece is one rare example of a situation in which the subject is a bit more

explicit.

The gallery’s floor has a symmetrical design of Venetian Terrazzo mosaic and its

main wall is accordingly divided in two by a door to the office. Taking a clue from

the premises, I divided my artwork in two parts (mindful that this was

corresponding to Dualism, one of my generic Translation Mechanisms).

Both parts of the installation had the same structure but differed slightly in some

details.

A large 12-foot high rectangle of cobalt blue was painted on either side of the

central door. On each of the two blues was loosely affixed the 10ft black/white

photomural paper of an enlargement of the frontal nude portrait of a male model in

a pose reminiscent of the David by Michelangelo. The models were two different

men, one of a slightly more Caucasian descent and one of slightly more African

descent. The photograph, shot by me in my studio, did not show their faces, in

order to avoid any anecdotal connotation.

The genital area was framed by a wooden helm the rungs of which had been

removed. Each of the six handles of the helm had the tip dabbed in pink shiny

paint.

Hanging at a slight incline over a black antislip strip on the floor to keep them

fixed in position, held by yellow ropes from the ceiling in the middle of the room

each in front of one of the nudes, were two 12’ by 4’ plywood slabs. They were left

raw but carefully sanded and painted with three coats of shiny red enamel.

Nowadays I think it’s almost impossible to find plywood of that size in normal

lumberyards.

At the same level as the genitals of the models, facing them, I glued a blinded

portrait of Sen. Helms. On one slab the portrait had an empty zone where the eyes

had been, on the other just a slit.

Behind each slab, on the back wall, a small rectangle of the same cobalt blue

framed the relocated rungs painted in green, almost like a kind of ritualistic

symbol, and below them the strip of the relocated eyes.

The Mechanisms here were the four colors + black/white + force of gravity +

relocation.

An intriguing footnote: the workers at the lab that normally printed my large

photo-posters refused to print these nudes. The manager found that indeed their

union contract stated that they can refuse to print frontal images of male (not

female) nudes. They allow only ¾ or side views.

She printed them for me personally on a weekend and we joked about the risk the

workers could incur in when developing a side view of the male organ if perchance

it isn’t in complete repose.

(11)

It’s important at this point to remind us that the goal of my approach to art is to

capture in every single, small or large detail or whole, the key to an emotional

pulse and to a leap of thought into dimensions that are unknown to me. We are

indeed here talking of the talkable but what can be described is not the aim of the

art, it’s only the instrument. Through matters that can be described I endlessly

strive for the powerful indescribable force that is hidden inside the making and

viewing of art.

(12)

One day I was exiting the DIA Foundation’s Walter de Maria Broken Kilometer

room on West Broadway with my adolescent son and I found myself surrounded by

a group of younger artists from Italy who had recognized me. There was Mimmo

Paladino and others. Then or shortly after I met Sandro Chia and Francesco

Clemente, later on Enzo Cucchi. Sandro and Francesco came to my studio a couple

of times. At a party Achille Bonito Oliva suggested I join the group. As always, I

preferred to avoid any group association. At that same party Julian Schnabel

invited me to his studio but I felt the invitation to be so very professional PR that I

declined. There were other connections: I had been exhibiting with Gianenzo

Sperone in Italy and some magazines I occasionally wrote for followed their works

as well.

(13)

By the same token I am sorry for those who sacrifice their creative impulses

censuring whole waves of invention in order to comply with the rigidities of

Consumer Fundamentalism.

(14)

Having worked with water-based paints for years I was wary of oil paint. Since the

70’s I had continued a conversation with Orin Reilly, the conservator of the

Guggenheim Museum. He was a very generous person and would spend long time

in telephonic exchanges with me. He told me how to mix oil paint. To exorcize my

fear, for these four paintings, Castles in the Air, 1978, I planned to insert a simple

design of geometric lines produced by sticking masking tape on the white-primed

surface and then cover the whole area with paint applied by a wide industrial brush

as if I had asked a passer-by in the street to fill it regardless of his/her knowing

anything about painting. After painting the colors, the removal of the tapes left

white geometric tracings.

For the blue panel I had planned to time my covering the large canvas with the

wide industrial brush. Then I was to fill a square left empty by masking it out in the

negative, white priming showing through, with black paint applied with a small

fine arts brush, timing it to take the same amount of minutes as used filling the

whole canvas with the blue.

When the piece was exhibited I liked the blue panel with just a white square in it

and left it so. It was exhibited again a couple of times. The last time was when the

curator Amy Baker had it installed in a corporate lobby committed to the

presentation of relevant art.

When the canvases returned to my studio, 20 years after having first been

exhibited, I decided that my original plan was what I preferred and filled the square

with black, slowly painted by a small brush.

The importance of not knowing is stressed in Zen and even more practically in

Shiatsu, when it is suggested that one empties one’s mind completely before

engaging in any endeavor. I push my not knowing even further by cultivating doubt

and indecision as sources of creative energy.

(15)

I have given whole lectures speaking Patchameena. It is for me a homage to my

brother, who was an extraordinary person and at the same time it acts like a

bracketing echo of how in the silent art of painting, sense and nonsense both

escape definition. The attempts to lock visual art into a describable subject matter

always fail as futile bureaucratic wishful thinking. Of course these attempts are

currently most fashionable in artistic discourse.

But what was Kingdom, the big installation upstairs at CR10 ? It consisted in long

paper scrolls onto which I printed photographs of portraits of Wilhelm Reich (the

German word Reich translates as Kingdom in English), of vegetables the shape of

which are sex-analogous and of Police from various countries in anti-riot attire.

The scrolls were all assembled near one another facing the entrance, all placed

towards the far end of the hall. I then scattered clusters of discarded common

furniture painted in the four colors elsewhere in the room.

The scrolls hung from the ceiling and upon reaching the floor extended onto it for a

couple of yards. A few touches of paint were added and small four-color fiberglass

casts of decorative fragments were sparsely strewn on the floor extensions.

Reich was an Austrian psychoanalyst follower of Freud whose insistence that

orgasm was a key to inner and social well being caused him great persecution. He

was banned by the Freudian Society of psychoanalysis and then kicked out by the

Communist Party. Being Jewish he came to the US seeking freedom when the

Nazis took power in Austria. In the US he was harassed by the puritan authorities,

was jailed with a pretext and died in jail in 1957.

(16)

It may be good to remind ourselves that distorted grotesque imagery is endemic to

art of all ages and all cultures before and after Bosch. The XVIth Century French

definition ‘grotesque’ in art came from the idea that in dark grottos, especially the

artificial garden caves, the rock formations may appear like dreamlike often

frightening images.

Most recently it appears wholesale in videogames, science-fiction and horror films,

posters and other media paraphernalia. I am interested in how distortions happen

while I paint or how memories of distorted features come to my mind whether I

seek them or not.

Like in everything I do, I don’t care much to be original in this because originality

as we intend it is merely a marketing device. I know that whatever I do always has

some origin somewhere, so I don’t worry about it. I can’t submit my thought and

emotion to clearing the copyright of imagery before letting it surface in my doing.

Nor do I pettily shout “I did it first!” the many times a manner or an idea I have

practiced is picked up by another artist and rewardingly continued.

(17)

My first exhibition happened in two sections. The first was titled Part One: Paint

Works and the second Part Two: Photo Works.

The diptychs were facing each other across the room, like mirrors.